When discussing threats facing the cinema business, Netflix, piracy and shorter release windows always seem to come before any discussion about hacking and cyber threats. Yet as cinemas increasingly rely on complex databases, social media marketing, online transactions, networked point of sale (POS) systems and automated operations of nearly every aspect of their cinemas, vulnerability to cyber threats is only increasing, while awareness and counter measures struggle to keep pace.

The latest example of the multitude of threats facing cinemas came to light last week when it was revealed that France’s largest exhibitor Gaumont-Pathé had become victim of an elaborate black market operation to sell cracked pre-paid and group cards to Pathé cinemas that would normally cost EUR €10 or more for only a euro or two. The hackers ran software capable of testing a large number of variations of the 12-digit code printed on the back of Pathé pre-paid cards until it found valid sequences. Customers that legally purchased and then tried to use a genuine card with the sequence would discover that the number had already been redeemed.

Pathé has not revealed how many cards were affected, claiming it was only a small percentage, but with 50 million tickets sold annually, that could still be a substantial amount. More worrying is that the scam is believed to have been operating for at least three years. It was outlined on the French cyber security blog Zataz a year ago. Gaumont-Pathé claims to have improved verification measures and compensated customers caught out, but Gaumont-Pathé’s Director of Operations François Bertaux acknowledges that “malicious people” have seen a “rise in the power of (their) digital strategy” of trying to defraud cinemas.

This attack was not an isolated incident, nor was it the most serious cyber attack on a cinema operator. Ster-Kinekor was the victim of South Africa’s largest ever corporate cyber attack when it revealed how a massive flaw in its old website led to the loss of privacy data for as many as 6.7 million customers. The attack was brought to light by software developer Matt Cavanagh, who discovered the flaw and alerted Ster-Kinekor of it before going public:

This wasn’t a hard thing to find at all… it was just pure negligence. Not only did the API [application programming interface] hand off details to anyone, they were also storing passwords in their database in plain text, and returning those to the client.

Details leaked included names, addresses, phone numbers, and plain text passwords, with 1.6 million associated unique email addresses exposed. Ster-Kinekor only acknowledged the damage when it had finished migrating to a new and secure system by Vista – though not without other problems. The hack was also reported on the website Haveibeenpwned.com where anyone can enter their email to see if a company storing their email has been hacked. Non-cinema companies that have been hacked in the past include Yahoo, Target, Dropbox, Adobe, last.fm, Brazzers and Domino’s – to mention just a few.

However, just because more cinema chains are not mentioned here does not mean that they have not, at some point, been hacked. It is just that those hacks might not have come to light or have not been disclosed. We asked cyber security expert Ben Rapp, CEO of Managed Networks, what the danger was for cinemas when it came to online threats. “Like all retailers who take payment cards, cinemas are a particular target for cyber-criminals,” he noted, further cautioning that “the growth of on-line ticket sales and membership/loyalty schemes also provides an attractive opportunity for data theft.” As Ster-Kinekor learned the hard way.

But a hacking can take many forms, other than just stealing personal data or cracking pre-paid codes. Here are some examples of other recent cyber attacks against cinema operators, ranging from big to small:

- A hack into a Shanghai cinema operator’s online system in early 2015 allowed thieves to siphon off CNY ¥1.47 million (USD $240,000) through third-party platforms. Beijing-based security consultant Chong Yu was quoted as saying that “this kind of thing happens every day.”

- South Korea’s CGV suffered a major network disruption that disabled its ticketing, booking, signage and app network on 28 September of last year. It is still unclear whether it was a hack or a network failure;

- A small Canadian cinema in Hyland had their website hacked in December of last year by someone who posted a rambling racist manifesto;

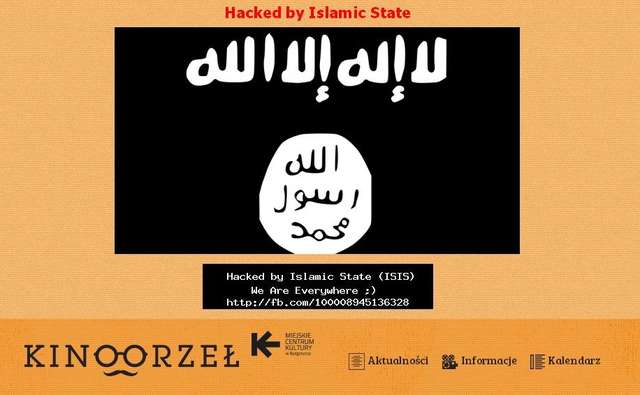

- A Polish municipal cinema in Bydgoszcz has found itself the unlikely target of a hack attack purporting to be from ISIS (Islamic State – see above);

- Hackers allegedly hijacked an outdoor screening in Argentina’s San Martin and replaced the comedy feature with an X-rated clip;

- The FBI investigated a cyberattack against this year’s Sundance Film Festival that shut down its box office over the opening weekend;

- And of course the alleged North Korean hack of Sony Pictures that cost it the scalps of several executives and millions of dollars of reputational damage.

These cinema hacks could be just the tip of the iceberg – and things could get much worse soon, not just due to hackers.

The Wall Street Journal noted in September of last year that “companies are getting hacked more frequently but aren’t disclosing the incidents in their regulatory filings, a trend that worries investors.” Obligations to report hacking vary from country to country and even from state to state, but the simple fact is that no company will want to voluntarily announce that they have been hacked and/or that their customers’ data was compromised. But even companies that have not been hacked face a danger if they are storing or handling their customers’ data improperly – not because of hackers but because of regulators.

This is the second way that cyber security could trip up cinemas, especially in Europe, where if they are not compliant with the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Adopted in 2016 it takes affect 25 May 2018 and means that any company or organisation collecting or handling personal data could be liable for major fines if they do not comply. How big? Up to EUR €20 million (USD $21.4) or four percent of the total worldwide annual turnover.

But with Europe’s three biggest exhibitors (AMC’s Odeon, Vue and Cineworld) based in the United Kingdom and Brexit around the corner, does this mean that there is less need to worry about GDPR? Not so, says Ben Rapp.

A recent survey of UK businesses showed that 44% of those who were aware of GDPR thought – incorrectly – that Brexit meant it wouldn’t apply. A similar survey in France found that 31% of CTOs weren’t even aware of GDPR, and that even the best-informed suffered from a number of misconceptions about the timing and scope of the Regulation.

In other words, even a cinema that is never hacked could still end up paying millions in fines for not having ensured that it is compliant with all relevant regulation such as GDRP. So, what should cinema operators do to make sure they are less likely to face cyber threats and/or regulatory non-compliance? Managed Network’s Rapp has some straight forward advice for cinemas: “Adopt the PCI-DSS security standard wholeheartedly. Make sure that their customer data, especially email addresses and passwords, is properly encrypted.”

However, Rapp also cautions against thinking that this is simply a technology problem to be solved and emphasises the need to focus as much if not more on staff and procedures. Cinemas should “give all of their staff regular cyber-security awareness training.” Above all, “make data security a board-level issue; don’t just leave it to the IT department,” he stresses.

In the interest of full disclosure and fairness, nobody is immune to hacking, as we discovered here at Celluloid Junkie. In researching and writing this article we found that our own site was compromised through a well known vulnerability called the Pharma Hack, some time between 2013 and 2014. No data was leaked, but the hackers were able to hide several rogue articles in our editorial archive with links that advertised certain brand-name male impotence pills. Needless to say we had not written or posted these articles, nor would you have seen or been affected by them, because they were strictly designed to be picked up by Google’s automated web crawler (googlebot). The plugin malware that caused it was removed long ago and our site is now clean, but the lesson here is that if you think your system is safe, it means that either, a) you are not aware of existing breaches, or, b) attackers have not yet succeeded, but are constantly trying. And they will continue trying.