The news that Germany’s UCI will roll out dynamic pricing to all of its 23 cinemas and 203 screens over the next five years marks the start of the embrace of dynamic pricing by the cinema industry. The fact that it comes the same week as Australia’s Village cinemas abandons its ill-conceived and poorly executed surge (not ‘dynamic’) pricing trial only serves to affirm this shift. Smart Pricer and its partners have demonstrated that dynamic pricing can work as well for the cinema industry as it already does for airlines, hotels, sports and e-commerce, but there are still challenges ahead for the industry as a whole.

The announcement made by UCI and Smart Pricer should not come as a surprise to anyone who has been following the dynamic pricing evolution in the cinema market. The companies have been carefully evaluating the concept over the past two years, first at just a couple of pilot sites and then gradually expanding the testing to more markets. “After observing over-proportional revenue uplifts and good customer acceptance at our test sites there is no doubt that our choice to partner with Smart Pricer and Compeso has been the right decision,” Class Eimer, Commercial Director of UCI, is quoted as saying in the press release.

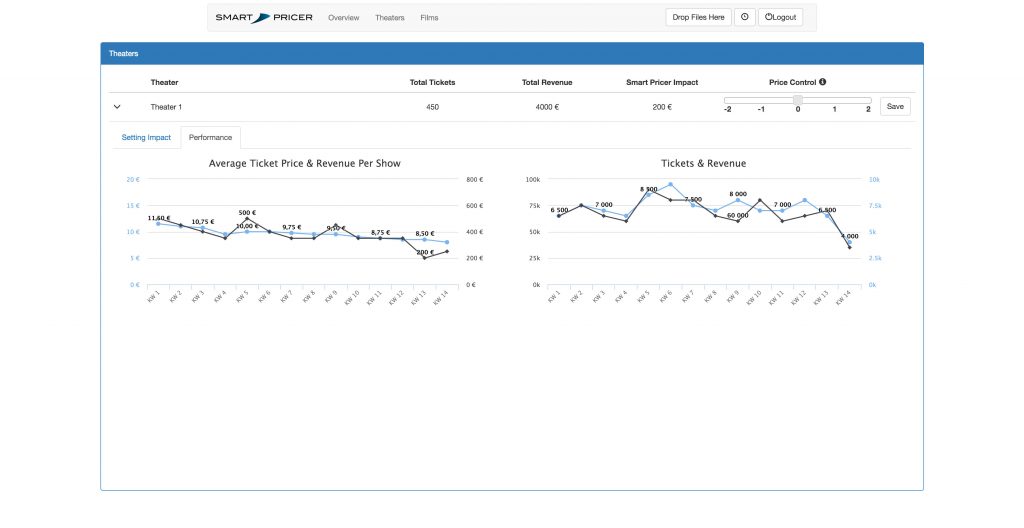

It is important to understand two factors of the tests that UCI, Smart Pricer and Compeso have been running. The first is that it has to be proven to make a significant increase to the box office over the long term through genuinely dynamic pricing flexibility, with Smart Pricer being able to point to as much as 5% incremental revenue, through A-B comparison of sites and shows.

The second point is even more important, which is to have all stakeholders onboard. In the first instance this means exhibitors, service providers like Smart Pricer and the ticketing and integration companies all have to work closely together. But equally important is it to have distributors onboard, who would fear that their intellectual property (i.e. the film) is being discounted or that higher pricing acts as a deterrent. Most importantly, as stressed in Eimer’s quote, is having the customers onboard by communicating clearly and transparently what the dynamic pricing switch involves and how it can benefit customers.

How NOT to Implement Dynamic Pricing

This last point was driven home clearly by the way Australia’s Village Cinemas was forced into abandoning its trial, after a consumer and media backlash branded their “surge pricing trial” as “greedy” and a “rip-off”. Compared to UCI and Smart Pricer’s success, Village’s strategy and execution – which appears to have been done in-house, without the involvement of a third-party – could be a textbook for business schools on the pitfalls of implementing dynamic pricing.

For a start, far from being ‘dynamic,’ the prices of tickets and concessions appear to only have been adjusted in one direction – upwards. Secondly, rather than testing the concept at one or two locations, this was launched at multiplexes all across the state of Victoria. Thirdly, rather than launching the trial during a quiet period when it wouldn’t attract the wrong attention, the pilot was launched over the busy summer school holiday season [N.B., Christmas is the warm time Down Under] with prices increased by up to one Australian dollar after 5 pm on Friday and Saturday nights. Finally, the trial was apparently not publicised, so when leaked internal documents showed up online it caused a public relations disaster.

Village Cinemas was forced to hastily cancel the trial and issue an apology of sorts:

Village Cinemas confirms that we were running pricing variation trials over the summer period which we appreciate may have caused angst and concern to our customers, we can now confirm that all pricing variation trials have been stopped effective immediately.

(In hindsight, using a Minion to accompany the purported internal memo may have doomed the trial from the start, as the yellow creatures are not famed for being able to plan and execute even the most basic of schemes successfully.) The overconfidence of bundling a surge pricing trial for both tickets and concessions, coupled with a lack of transparency, has thus caused trust erosion and brand damage. As Andrew Birmingham put it in his Which-50 opinion piece, “Arrogance, poor service, and bad decision making dressed up as innovation. This is why incumbents fail.”

The failure of the Village Cinemas trial is all the more surprising given that simply bumping the ticket price during busy times or having ‘tiered’ pricing is already common practice amongst exhibitors, both in Australia and elsewhere. Hoyts Cinemas charges AUS $15 (USD $11.79) for “The Greatest Showman” at its Eastland multiplex on a Friday lunchtime, but AUS $4 (USD $3.14) more three hours later. In the UK Odeon has been accused of adding a ‘blockbuster tax’ since 2014 as Metro reported last year that “[a]n Odeon spokesperson told us that their ‘flexible pricing policy’ has been a thing for last three years.”

Note though that Odeon calls this ‘flexible pricing policy’, rather than ‘dynamic pricing’, making it slightly less misleading. Given that the price of cinema tickets is a much complained about subject in Australia, introducing ‘surge pricing’ rather than genuine ‘dynamic pricing,’ wherein some tickets are also cheaper, is a recipe for disaster. Village was left to feebly point to its Vrewards and discount programmes as a fig leaf for its price hike trial.

Compare this to the positive coverage that the UCI announcement got in Germany, where Kinofans.com (self-proclaimed “site for the film fan”) ran the headline ‘UCI Kinowelt introduces discounts for early ticket booking‘, which is the ‘glass half-full’ perspective on dynamic pricing. It goes on to point out that there will be no more long queues at the box office and that those that plan and buy in advance will be rewarded, compare to those that just show up on the day of the screening to buy the ticket (with the noted exception of Star Wars fans). This is the kind of message that cinema dynamic ticket pricing should be communicating.

Regal and the Perils Ahead for Dynamic Pricing

Dynamic pricing got the most attention recently when Regal announced in November of last year that it was testing dynamic pricing in partnership with Atom tickets. As we wrote at the time (‘Some Advice For Regal Cinemas On Dynamic Movie Ticket Pricing‘) cinemas have to tread carefully around dynamic pricing to avoid being tarnished as simply ‘surge pricing’, commonly associated with demand-driven platforms such as Uber, or ‘gauging’, rather becoming commonly accepted industry practice, as is the case with flights, sporting events, hotel rooms and (whisper it) e-commerce.

Smart Pricer’s Christian Kluge, speaking exclusively to Celluloid Junkie at the time, advised four concepts to keep in mind: communication is the key, localization, test small – scale big and finally data ownership and front-end control. Yet this announcement and our article inevitably led to more industry discussion and questioning, which is worth examining as exhibitors take two steps forward and one step back in the direction of dynamic pricing.

My colleague Jim Amos, who predicted that 2018 will be the year dynamic pricing launches in the US (prior to the UCI announcement), also raised questions about how it will be effectively implemented. Just like airlines, different times will have different bands of prices, but different seats on the same flight/show will also have different prices. Reserved seating is thus a necessary first step prior to introducing dynamic pricing. But unlike airlines, which has stewards and stewardesses to ensure people don’t sneak into Business or First class, cinemas will not have ushers permanently on guard to ensure that premium seats do not get taken by people who have paid for cheaper ones, whether they are at the edge of the cinema or are no-nrecliners. So unless the cinema is sold out, will audiences have to be trusted to self-police seating?

This question lead to an informative and detailed discussion on LinkedIn where Smart Pricer’s Kluge shared some of his company’s experiences in different markets outside of the United States where this has been tested:

We believe there are two degrees of differing prices for different seats in one auditorium:

- Having a section of physically different VIP/Premium seats (e.g. reclining, more leg space and so on) is already common practice in many European and Asian markets. Typically they sell at a +20 – 40% price surcharge on top of what a seat in the standard section of the same screen would cost. Check out www.cinemaxx.de or https://uae.voxcinemas.com/

- In some markets e.g. Germany, Malaysia, partially also Russia, exhibitors go even further and price front and side seats differently from back and middle seats. Those seats are physically the same, just the location within the screen is different. See for example http://cinemaxx.ru/

All these exhibitors use reserved seating. In our talks with cinemas applying both 1) and 2) most acknowledge that there is some reseating to better seats than paid, but only to a limited degree. Overall, most were happy with bottom-line impact.

There are still issues in terms of cinema culture. Remember that reserved seating has been common practice in some countries, whereas in other countries like the US and France it has only been introduced more recently and also led to some consumer pushback.

The Future of Dynamic Pricing in Cinemas

One could devote several articles to all the questions (and answers) surrounding the ins and outs from of dynamic pricing, so much so it is surprising that Smart Pricer has not put up an FAQ on its website. Surely they must have answered variants of the same questions countless times. Two examples are, won’t people and staff be confused about what ticket price is when buying at the box office, and, why discount advance tickets when Star Wars fans who pounce when “The Last Jedi” tickets are released are the ones who would be ready to pay the most.

In the case of the former, it works because more and more tickets are sold online or on-site through ticket kiosks and besides, cinemas don’t have fixed prices on light boxes above the till any more. In the case of the latter, you can get discounted flight and hotels by booking early, but if you are planning to fly to Paris for New Year’s Eve and stay at a luxury hotel, even booking six months in advance won’t get you that super bargain.

One of the interesting things about the UCI announcement is the implications of the speed with which dynamic pricing could now spread. UCI is part of the Odeon Cinemas Group, owned by AMC/Wanda. The parent company makes a point of evaluating best practices in the global group and then deploying it rapidly with other parts of its worldwide family. This means that the success of Imax and Dolby Cinemas in China acts as a catalyst for speeding up deployment with AMC in the US, while the recliner programme in the US sees a variant of it implemented at Odeon in the UK and the Nordic Cinema Group (NCG) in Scandinavia.

The decision by NCG’s co-owned Svenska Bio to go 100% cashless (after a similarly careful trial) at the end of 2016 has been carefully studied internally by AMC/Odeon/NCG. Yet the spread of such local best-practices are not immediate, because senior management at Wanda/AMC/Odeon/NCG knows that there are significant cultural differences to cinema markets. The mobile ticket buying that works in China can work in Sweden but will take longer in the US, while going cashless is definitely not an option for UCI in Germany. Yet dynamic pricing has the potential to be spread more widely and quicker than other cinema innovations. The hope is that the model followed is closer to that of UCI-Smart Pricer and Compeso in its execution rather than the example Village Cinemas has set for the industry.