A UK study just released has found that screening opera in cinemas is not boosting the interest to attend performances in actual opera venues. The research would seem to provide ammunition to those who claim that event cinema screenings of Met and Royal Opera House productions is cannibalizing audiences from regional opera productions and is not increasing interest in the art form as a whole. However, a careful reading of the findings and underlying numbers provides a more complex picture.

The study called “English Touring Opera – ‘Opera in Cinemas’ Report” (Dropbox .DOCX link) is a research project undertaken by English Touring Opera and the Guildhall School of Music & Drama, in partnership with the Barbican Cinema, and funded by CreativeWorks London. While the report does not make it explicit, the English Touring Opera has a particular interest in this issue. In the pre-digital age, people who did not live or or could travel to London or one of the few other major UK cities with its own opera house, had to make do with local amateur productions or the touring opera.

The research was conducted through both questionnaires and focus group discussions. There is much data and analysis from the former, while the latter provides insights into participants views and opinions, with plenty of direct quotes to back up specific findings. At 23 pages it is worth reading in full and even to go through all the statistics. We won’t try to summarize everything, but to highlight some of the interesting findings.

Finding: Opera in Cinema is not a ‘Gateway’ to Opera in Person

The study took a focused view in terms of audiences, productions and locations.

Participants came from 13 different cinemas (4 outside London), with the majority (46%) drawn from the Barbican as partner (see Fig. 2). Participants from outside London only numbered 13 (5.5%). Most (160; 68.4%) were subscribers or part of a loyalty scheme at the venue, and 79.1% were repeat attenders to the venue for opera screenings. In addition, 64.5% reported having attended a live opera relay elsewhere.

There were five opera screenings that were included, the response rates for which can be seen in the graph below.

Those polled were turned out to be mostly frequent attendees of opera screenings, with a significant majority having attended 10 or more screenings in the last couple of years.

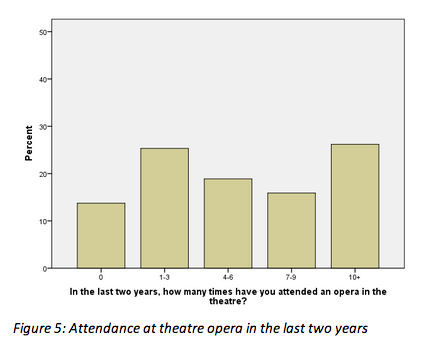

When it came to the same audience being asked if they had attended an opera in person, there was a more even spread in terms of past attendance.

The survey then focuses on the ‘values and quality’ reasons for cinema opera attendance, with an intricate Map of Themes. Four themes emerged, which are extracted and summarised below:

1. There is nothing like live opera in the theatre – cinema can only ever be second best to this.

2. Cinema is a good alternative to live theatre for those who cannot afford or access the opera house – some aspects don’t translate but it gives a fairly good approximation of the experience of being there (brilliant, but not the same as live)

3. Cinema opera is a new art form, a genre in itself. It offers something different, but equally valuable or even better.

4. The potential of cinema to be good for newcomers, overcoming stereotypical perceptions of opera, and break down barriers to attending.

The survey then moves on to content analysis, looking at the open-ended questionnaire questions and the responses. This takes into account aspects of the performance itself, film and camera work, extra footage, cost, liveness, sound, physical comfort, audience and many more factors. Some unintentionally amusing views can be glimpsed in between reading the formal findings, such as opera purists being annoyed at grannies who bring in sandwiches to munch on during the performance.

The findings are distilled into a table of what factors most influence people’s’ decision to watch an opera in the cinema.

Here it is worth quoting the report at length because it provides pertinent insights into how preferences translate into actions (or not) for cinema and opera.

The implications of this analysis are borne out by a correlation analysis showing that each of the starred items in the table above correlates significantly and negatively with reported level of theatre attendance across the whole sample, but not with reported level of cinema attendance (even though cinema and theatre attendance are significantly positively correlated with each other). Thus people’s perceptions of the importance of value for money, affordability, accessibility, venue and time are systematically related to their level of theatre attendance: the higher the level of importance they attach to these, the less frequently they attend the theatre. But the importance of these factors is not related to how frequently they attend the cinema (even though we asked the question in specific relation to their decision to attend a cinema performance). Although we cannot establish a causal link, the implication is that people’s judgements of these aspects are a factor in their attendance at the theatre. But some people’s judgements may not be based on accurate opera-going experience, since they don’t attend. Therefore an opportunity exists for ETO to replace judgements based on little information with targeted messages.

This is where things get interesting and the real debate starts.

The Controversial ‘Conclusion’

The two critical paragraphs come in the section 4 iv. Changes in motivation to attend future cinema and theatre opera performances

Participants were asked whether their motivation to attend cinema and theatre performances of opera had changed as a result of attending the cinema screening. The majority of responses for each were ‘about the same’, but there were slightly more reports of increased motivation to attend future performances in cinema than in theatre (Figs 7 & 8). First time cinema attendees, however, showed a different pattern, with 67.8% reporting increased motivation to attend cinema screenings in the future (46.4% being a ‘lot more’ motivated) (Figs 9 & 10). Their motivation for attending future theatre performances remained largely unchanged… [added emphasis]

And

In sum, the implication is that attending cinema relay is more likely to inspire further attendance at a cinema rather than encourage people to transition to a theatre experience. In line with this, a sizeable minority (25.1%) of participants who hadn’t attended a theatre performance in the last 2 years reported feeling less motivated (18.8% ‘a lot less’) to attend future theatre performances, with only 12.5% feeling ‘more’ or ‘a lot more’ motivated. [again, added emphasis]

It is this finding that The Stage chose to highlight in the article about the report.

Around 85% of audiences that attend live screenings of opera do not feel more compelled to see the art form live afterwards, according to a new survey.

The investigation found that, after seeing an opera at the cinema, around 75% of participants reported feeling no different about attending a live production, with around 10% feeling less motivated.

This has shown that screening opera productions to create a new generation of audience for the live art form is “wishful thinking”, according to English Touring Opera’s general director James Conway.

Taken at face value, this would seem to be a pretty damning indictment of opera screenings. But do these figures tell the whole story?

What the opera cinema companies are saying

Celluloid Junkie reached out to Christine Costello, Managing Director and Co-Founder of More2Screen, which is one of the leading players in the event cinema market with several operas under its belt, to get her take on the report. Her comment was that

‘For us, this research underlines again how important cinemas are to making the opera experience accessible , affordable and a more frequent date in the social calendar for its loyal audience . The improved quality of filming for the big screen, inclusion of behind-the-scenes extras and the development of specially curated cinema seasons have played an enormous part in broadening the appeal of Opera for local and global audiences’’

The report is likely to be poured over by both event cinema distributors, as well as by the premiere opera houses (Met, ROH, ENO, La Scala, etc.), many of whom are likely to have conducted their own internal audience surveys in both cinemas and in their native venues.

However, until these are released or the findings shared, we will not know how they square with this report.

Response From the Event Cinema Association

Wanting to dig deeper, CJ contacted Melissa Keeping, head of the Event Cinema Association (ECA) to get her organisations take on the somewhat controversial findings.

She pointed out several aspects that might not be immediately apparent on the first reading of the report, while at the same time challenging some of the conclusions in The Stage article.

The first one is perhaps the most obvious, which is that the study was invariably restricted, in terms of sampling a small pool of just 230 participants, almost exclusively only based in London. As such, Keeping notes, it is “hardly representative of the tens of thousands of cinemas worldwide that are routinely sold out for all manner of live events, not just opera eg.”

This does not invalidate the findings, but puts the in perspective. Above all it highlights the need for a further and broader survey conducted on a far larger scale. Not just in the UK. “ROH alone has 1000+ cinemas in 30 countries,” Keeping observes.

Secondly, Keepings points out that “Event cinema is still very nascent, not even 10 years old yet and it’s only entered a phase of relative maturity in the last year or so.” As such, she says, it is too early to make sweeping statements, like the ‘Opera screenings failing to boost interest in the art form, survey finds’ headline of The Stage article.

Again, further surveys would be needed to study changes in behaviour over time, as any statistician will tell you that peoples’ stated intentions and eventual actions can differ greatly.

That said, the ECA is not outright rejecting the findings of the study. “There are always things we can learn, and even the most experienced provider of content would agree that striving for improvement is a central factor in the creation of great art,” is how Keeping puts it diplomatically.

The ECA is widely acknowledged to have done a lot for the event cinema industry, not least in providing data and research. As such it is highly likely that it will take an active role in promoting future studies and polls amongst opera screening attendees.

Selective use of quotes and a more balanced headline

The English Touring Opera’s take is less strongly worded than The Stage article, which derives most of its figures and quotes from it. Their own press releases is called ‘New research suggests work needs to be done before cinema broadcasts bring in new audiences for opera’, which is a far more constructive take on the data and findings.

The Stage is also very selective in how it quotes ETO’s general director James Conway and could even be accused of selective quoting. Here is his response in full.

“A lot has been speculated about the potential for cinema relays to create new audiences for live opera. I would love that to be the case but, as this research indicates, it may be wishful thinking.

“What is sure is that access to digital opera performance has changed quickly, and producers of opera will need to respond with some intelligence to an environment that has not transformed, but has certainly shifted.

“This partnership with the Guildhall School and Creativeworks London has been vital as ETO starts to formulate its response to these changes and our future business development.”

There is a significant difference between calling something ‘wishful thinking’ and acknowledging that “it may be wishful thinking”, which effectively says that ‘we can’t be sure.’ The response effectively aknowledges that more research is needed, so that it can help opera companies tailor their offerings for the demands of audiences in the digital cinema age.

Digging deeper into the statistics and conclusion

There are many other interesting thing about the data that have not been highlighted. The most shocking (or not) is the age of the sample group.

The largest group of attendees were 60-69 and there were more people in the age group 80 and above than the combined attendance of those under the age of 50. Furthermore, the number of people in the age group 20-29 and 30-39 categories were practically a rounding error.

The reasons for the popularity of opera in the upper age category are explained in the focus group contributions, such as this one.

Although a cinema screening of opera can never be as thrilling as a good production in the Opera House, it is an excellent second best. I am too old to travel abroad for opera and also opera house tickets have now risen to a price outside my budget. Have given up my membership to the ROH and the ENO and am very grateful that I can still hear some excellent productions from the MET (Barbican, Eugene Onegin, E79)

While it is no surprise that opera thus attracts an older crowd and that pensioners have more time on their hands than people with children, this study should point to a clear need for audience development. With cinema putting world class opera within reach of anyone who can make their way to a cinema, there is more need for school, volunteer associations, music societies and others to encourage opera attendance.

The report does find that while opera-in-cinema might not lead to opera-on-the-stage attendance, it does serve as an excellent entry point for people who never attend opera.

Most of the focus group participants, and a handful of the questionnaire respondents, reported bringing others to their first experience of opera through the cinema – and that these people were resistant initially and then surprised by the reality. Cinema was felt to offer a way in to opera because of its familiarity as a medium, its democratising nature, and its more relaxed atmosphere. However, there was acknowledgement that this alone was not enough for people to just ‘walk in off the street’. There was also a subtle perception among participants that opera is something one needs to be educated about, and initiated into. Newcomers are referred to as ‘novices’ or ‘beginners’, and they themselves report using cinema to increase their knowledge and ‘feel more confident’.

Just because a cinema is screening an opera does not automatically mean that it will attract the same demographic watching Maleficent in the same building.

It should also be remembered that many of the most acclaimed operas tend to get sold out quickly and that tickets might thus only be left for more obscure operas that are harder for novices to enjoy, compared to, say, a Carmen or La Boheme.

Furthermore, the report highlights the things that people, particularly novices, like about opera in cinema. It is thus encouraging enough that they would like to see more of that – in the cinema. To expect people to pay more to still only be able to afford a seat up in the ‘nosebleed section‘ of the actual opera house is perhaps expecting too much.

The more important question, which is not fully addressed in this report, is the impact of watching world class opera in the local cinema is having on attendance of local, regional and touring productions away from the major cities. There can be no disputing that the overall number of opera attendees has increased thanks to digital cinema, but to what if any extent they have cannibalised attendance of local productions is still unknown.

What the report does point towards is the need for an on-going audience development, particularly targeting school children, as well as further research in this field. The English Touring Opera et al should be commended for getting the ball rolling.