In 2011 the average ticket price in China was CNY ¥37 (USD $5.62) but by 2015 this had fallen to nearly CNY ¥35 (USD $5.32) despite the growth of Imax and premium screens and the increase in cinema ticket prices in all other major economies. Mobile ticketing by third-party vendors is the main cause, but rather than distorting the market, a new paper by H. Brothers Research (or HDresearch, from the Huayi Brothers Institute) argues that this has been necessitated by changes in the Chinese cinema market.

With 278 films released in 2015 across 30,000+ screens belonging to more than 40 major exhibitors there is still fierce competition for screen space with the Top 10 films accounting for 28% of total box office, meaning that other films go ‘begging’ for bookings. This means that the first week (effectively first three to five days of release) are critical for any new films to stand a fighting chance of recovering it costs. This is all the more so as the ancillary market for film in China is under-developed compared to western economies.

The transition from 35mm film to digital projection has also meant that there are virtually no cost constraints on the number of copies (DCPs) that are distributed to cinemas. This in turn has eliminated the market for secondary cinema runs in progressively smaller cinemas, all the way down to prints being cycled between small village screens. The same film now opens in both tier-one, -two, -three and -four cities across China.

Distributors thus have to come to terms with distributors, often by agreeing to rental terms where the splits strongly favour the cinemas. Only then will the exhibitor commit to releasing the film widely, though this is still no guarantee that the distributor might not end up losing out because of box office fraud through ‘concealed’ revenue. Exhibitors might even refuse to show the film at the last minute, extracting further discounts from the distributor in blatant arm-twisting tactics. As such, the absence of clear and binding provisions guaranteeing plays of the film is the biggest difference between the Chinese and the North America cinema markets.

Since the reform of regulations relating to cinema building and operation in China in 2002 there has been a surge in the number of new screens, with nearly six years of average annual compound growth rate of 38%. But this is underpinned by huge upfront investment costs and payback period of just three to five years in many cases. While some cinemas receive subsidies and incentives from various levels of government, they are still under pressure to deliver rapped returns. With the concessions, advertising and event cinema market under-developed compared to the West, Chinese cinemas thus rely excessively on box office revenue to achieve profit.

HDresearch argues that there must be more stable contractual terms between all parties in the film distribution chain, from producers, through distributors to cinemas, not least in order prevent a ‘bubble’ (the Chinese character is ‘foam’) from growing. Rather than a winner-take-all mentality, the paper argues for helping to grow the cinema cake together so that all parties can benefit. It argues for strengthening of industry bodies (associations and consortiums) in order to promote dialogue between the various players.

While the role of the third-party commerce platforms is not discussed in-depth, the block-buying and re-selling of seats gives both distributors and exhibitors a degree of certainty of revenue, particularly for big budget blockbusters released during holidays or special periods, when operators such as Guwera and Cat’s Eye offer special deals for CNY ¥19.90 (USD $3.00) or even CNY ¥9.90 (USD $1.50). But this will only be the case for as long as their is competition for customers between the commerce app operators and they are willing to subsidise each cinema ticket. What happens once that ends is not a topic for this H.Brothers Research paper. But it certain that Chinese cinema ticket prices cannot continue to go down forever.

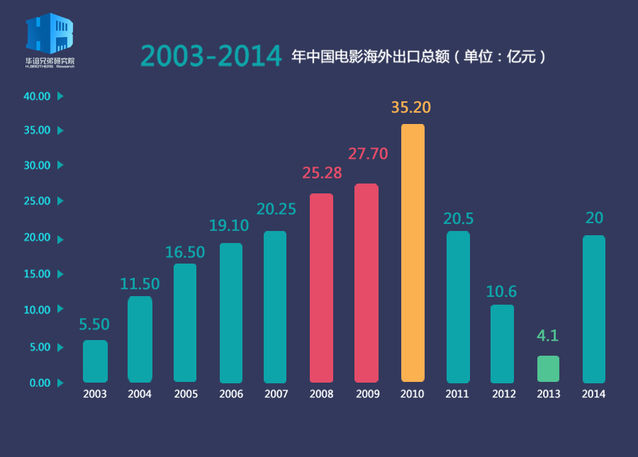

In a separate research paper HBresearch argues that while China’s cinema market has previously grown as fast as other government-supported major infrastructure projects (railway, airports, highways), the end of this growth cycle is in sight and there are requirements for “supply-side reforms”. This is primarily grounded in seeing a better quality of domestic blockbusters that can compete more effectively with Hollywood films at the box office. With Huayi Brothers being one of the leading Chinese domestic film producers and distributors there is a level of self interest in what is at stake. But there is also recognition that seeing how strongly South Korea’s domestic film industry is doing in direct competition with Hollywood movies, there is scope for China to learn and up its game ahead of the next round of renegotiating the import quotas of foreign films in 2017.

The days of the biggest cinema building spree may be behind it, but China still has an opportunity for a quality boom in the local films that will play in these multiplexes in the coming years.