The United States Department of Justice (DoJ) has filed a lawsuit with the aim of blocking the proposed USD $375 million merger between US cinema advertising majors National CineMedia Inc. (NCM) and Screenvision LLC. NCM admitted to being both “disappointed” and “surprised” by the decision, but predicted that the case could be overcome within “four months or possibly more,” setting the stage for what could be an interesting court battle.

The DoJ move shows that, whatever the merits of the deal, NCM has not made a strong enough case as to why “eliminating competition that has substantially benefitted movie theaters, advertisers and, ultimately, movie goers” (in the words of the DoJ) should be allowed to be replaced with a de-facto monopoly for cinema advertising in the US.

The DoJ’s Case Against the Merger

The DoJ issued a strongly worded press release on Monday 3rd of November after the DoJ Antitrust Division’s lawsuit was filed in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York.

“The proposed combination of NCM and Screenvision is a bad deal for movie theaters, advertisers and consumers. This merger to monopoly is exactly the type of transaction the antitrust laws were designed to prohibit,” said Assistant Attorney General Bill Baer of the Justice Department’s Antitrust Division. “If this deal is allowed to proceed, the benefits of competition will be lost, depriving theaters and advertisers of options for cinema advertising network services and risking higher prices to movie goers.”

As the press release points out, the proposed merger is between two majors that control cinema advertising in “88 percent of all movie theater screens in the United States through long-term, exclusive contracts.” What the press release does not say is that while this merger covers 88% of total US screen count, these screens represent a higher proportion of box office, cinema attendance and prime audience demographic, which is what matters to advertisers.

The DoJ is methodical in laying out why during the past few years competition in the US cinema advertising sector has been so strong:

Over the past two years, competition between NCM and Screenvision intensified as Screenvision became a particularly aggressive competitor, increasing its efforts to steal business from NCM by dramatically reducing the prices it charges advertisers and offering movie theaters a variety of attractive financial incentives. The complaint contains statements from NCM’s and Screenvision’s executives describing the competition between the two companies and the motivation to end that competition by entering into the transaction:

- Aggressive competition between NCM and Screenvision for movie theaters led NCM to observe that “we need to buy [Screenvision] before either us or [Screenvision] does a stupid deal.”

- By April 2014, NCM arrived at what it called a “Strategy Decision Crossroads.” As NCM had told its board it could either acquire Screenvision, which would give NCM the ability to “Control Selling Tactics,” including “Pricing,” or it could compete through more aggressive pricing and adding theaters to its network. NCM chose to buy out its competitor.

- NCM viewed Screenvision’s “new strategy of undercutting [NCM’s] pricing by 50 percent (or more) [as] a direct threat to [NCM’s] business model” and “a very unusual strategy in a duopoly.”

The implication is that NCM is not pursuing the merger so much to unlock synergies and better compete with television and online advertising, as to get rid of pesky competition that is eating into its bottom line.

The DoJ believes the proposed merger would lead to “advertisers paying more for cinema advertising and movie theaters receiving less revenue,” which in turn is likely to “result in movie theaters having to raise ticket or concession prices to consumers or forego theater upkeep and improvements.”

NCM (and Screenvision) Caught by Surprise

The announcement did nothing if not catch NCM and its would-be acquisition by surprise. There had been both internal and industry-wide expectations that the deal would be approved, perhaps with some conditions attached.

It should also be remembered that this proposed merger comes against a backdrop of much larger proposed mergers, primarily that between Comcast and Time-Warner Cable, which is widely expected to be approved, as was the merger of AT&T and DirecTV. Instead the DoJ took the same line as it did in 2011 in the case of the proposed merger between AT&T and T-Mobile, signifying that it is prepared to take a tough stance in some cases.

What particularly surprised, and perhaps irked, NCM was the outright ‘No’ from the DoJ, rather than a discussion about or suggestion of proposed concessions. NCM’s CEO, Kurt Hall, made this clear in a conference call with analysts shortly after the DoJ announcement, as reported in Deadline.

As for the DOJ decision, “honestly it was a little bit of a surprise that it came out this way,” Hall told analysts in a conference call. NCM wasn’t asked to make any concessions and is unaware of any opposition from outsiders. “We feel very confident that our arguments continue to be strong and clearly some of the claims that the DOJ has made can be proven incorrect or misguided. That will be our job over the next several months.” If the deal falls apart then NCM has to pay Screenvision a $28.5M breakup fee, “but we’re a long ways from that.” The companies had hoped to close the deal around now; they now say that will have to wait about six months for a court decision.

Expect lawyers to further profit from the delayed merger as they re-build a case for the union in front of a judge.

Possible Concessions (Not the Popcorn Kind)

The problem is to envision what sort of concessions could make the proposed merger acceptable to the DoJ.

If it was a case of two cinema circuits merging they could be asked to sell of properties in markets where they would dominate. But NCM with USD $426 million in advertising revenue taking over the smaller Screenvision (USD $160 million in revenue) could not spin off part of the latter’s advertising business without defeating the object of the merger exercise. There is also no third significant cinema advertiser (leaving aside Canada) to sell a portion of the business to.

This leaves just two options for possible concessions.

The first is to sell off NCM’s alternative content (event cinema) Fathom Events business, to give the company less total sway over US exhibitors. NCM would like to do that anyway and has spun it off as a separate entity – though it still holds a big stake, together with NCM’s founding exhibitors – but even merged with Screenvision’s event cinema arm it is unlikely to be strong enough to stand on its own (yet) as a publicly listed company. This means that a venture capital or private equity owner would have to be found, which would not yield the sort of sale price NCM and the other owners would be hoping for.

NCM’s Fathom Events would also not be able to take on all of Screenvision’s event cinema contracts and relations, because of non-compete clauses that would prevent a merged operation from for example offering operas from two competing opera houses in the same season. It is also unlikely that this by itself would placate the DoJ as it still does not fundamentally alter the arithmetic of a screen advertising monopoly.

Secondly, the three theatre circuits that are the ‘Founding Members’ of NCM – Regal Entertainment Group, AMC Entertainment Inc. and Cinemark Holdings Inc. – who also control the majority stake in the company, could be forced to divest themselves of their ownership in NCM Inc. (they owna a 45.8% interest in and are the managing member of National CineMedia LLC).

This would mean that while NCM Inc. would still be a de-facto monopoly it would operate at more of an arms-length to all US exhibitors. It should be remembered that there is no law against monopolies per-se (or else Microsoft would not have controlled the PC market with Windows), only against the abuse of a monopoly position (as was the case of Microsoft bundling the Explorer web browser with its operating system).

Yet if Regal et al were forced to sell off NCM Inc. prior to it accruing value through the merger with Screenvision the purpose of the merger (to maximise value for existing shareholders) would be lost. So this would be a non-starter for the companies founding members.

NCM came closest in offering an olive branch by saying that the company was willing to extend its revenue sharing agreements with theaters “or make other improvements to the exhibitor terms to ensure that there is always a complete alignment of financial incentives and interests between us and our theatre circuit partners.” But it will have to become much more concrete to convince DoJ that the offer is sincere and credible.

So for now it really seems like NCM can offer little in the way of concessions to the DoJ – other than the snack variety – which may be why the DoJ did not raise the issue in the first place.

Where the DoJ Goes Wrong

The DoJ is wrong in thinking that a merged NCM 2.0 could extract significantly more revenue from advertisers, and should be blocked on this ground, because pricing elasticity does not hold when the same advertisers can get more eyeballs for less dollars on television or online.

Cinema advertising is a premium medium and already commands premium prices, but in return offers a more captive audience with higher impact and recall. Anyone who has ever talked to a cinema advertiser knows that despite compelling statistics that demonstrate a dollar spent on cinema advertising offer higher ROI (return on investment) than the same dollar spent on broadcast, cable, internet or mobile ads, selling cinema advertising is still hard.

NCM’s CEO Kurt Hall is thus right to contrast the 400 or so brands that advertised in cinemas in the past year with “thousands of brands [that] buy TV networks and mobile video advertising platforms each year.”

Both NCM and Screenvision have to fight hard and earn every one of the brands that end up on the big screen, not least with media buyers in agencies finding it easier to book with broadcasters or cable channels, if not hearing the siren call of programmatic buying towards online and mobile platforms.

So advertisers and brands would not by any stretch of the imagination be significant ‘losers’ of a proposed NCM 2.0 that included the digested remains of Screenvision. The bigger question is where it would leave exhibitors and by extension audiences. (More on this later).

NCM, Screenvision and Carmike Fire Back

The response from NCM and its would-be mergeree was swift and strong. NCM and Screenvision almost immediately put out a press release defending the proposed merger, though the tone was one of regret and conciliation rather than attack.

NCM Chairman and CEO Kurt Hall said, “I am obviously very disappointed that the DOJ did not see the benefits of the new combined company to our advertising clients and their agencies and our exhibitor partners. We look forward to demonstrating those benefits. Combining NCM and Screenvision will enable us to offer advertisers a better product with the broader reach, ubiquitous geographic coverage, more advertising impressions, enhanced targeting capability, and lower costs that advertising clients and their agencies seek. With a better product we will generate more advertising revenue for our theatre circuit partners. Advertisers, exhibitors and shareholders all will benefit from this combination which will better enable NCM 2.0 to compete in the increasingly competitive video advertising marketplace.”

(It is worth asking whether NCM and Screenvision would have done themselves more of a favour by putting out separate press releases, to make the would-be merger seem like less of a forgone conclusion, but it is clear that the two want to be seen to be singing from the same proverbial hymn sheet.) Screenvision’s CEO Travis Reid thus echoed Hall.

“The merger preserves all the desirable attributes of cinema advertising while allowing the combined company to compete more effectively on dimensions important to advertisers. Together, NCM and Screenvision will be more competitive in the expanding video advertising marketplace and provide long term incremental advertising revenue to our theater partners.”

This sentiment was further echoed by Carmike, the largest exhibitor shareholder in Screenvision with its 19% “profit interest” in Screenvision’s holding company SV Holdco, LLC, as quoted in MarketWatch.

David Passman, Carmike’s President and Chief Executive Officer, stated, “We are disappointed that the DOJ is seeking to block the proposed sale of Screenvision. We hope that Screenvision and NCM will be able to demonstrate the benefits of the transaction to the DOJ. However, we are very pleased with our existing relationship with Screenvision and, in the event the proposed sale is not consummated, we look forward to continuing to work with Screenvision in the future.”

Carmike needs the money from the Screenvision sale to fund its expansion and improvements to its circuits, so this delays will be particularly unwelcome news for Passman.

The NCM-Screenvision press release spells out five major points, around which the lawyers will presumably build their case for the merger in court. By headline, they are: 1) Greater Reach; 2) Ubiquitous Coverage; 3) Ability to Target Specific Audience Demographics; 4) Lower Costs for Advertisers; and 5) Significant Expense Synergies. Notice also that the first three points quite clearly spell out the issue of competing with television (and online), though they still read more as pitches to advertisers and brands, rather than placations to the DoJ.

The lawyers will also presumably all but drag a senior television executive to court to testify how irrelevant cinema advertising is in the greater advertising scheme of things, to make their point that they are the smallest of all national ‘broadcast’ channels.

Consider that compared to NCM’s USD $426 million annual revenue last year, MSNBC’s revenue in 2012 was USD $443 million, and that’s for a news network struggling against CNN and Fox News, not to mention earning significantly less than the big networks ABC, CBS, NBC, Fox and even CW.

Market Reaction and Quarterly Results

The DoJ announcement was unfortunately (deliberately?) timed to coincide with NCM’s quarterly results, with the effect of shifting the earnings call with analysts from Tuesday to Monday, where the topic dominated. Again from Deadline Hollywood (which had excellent coverage by David Lieberman):

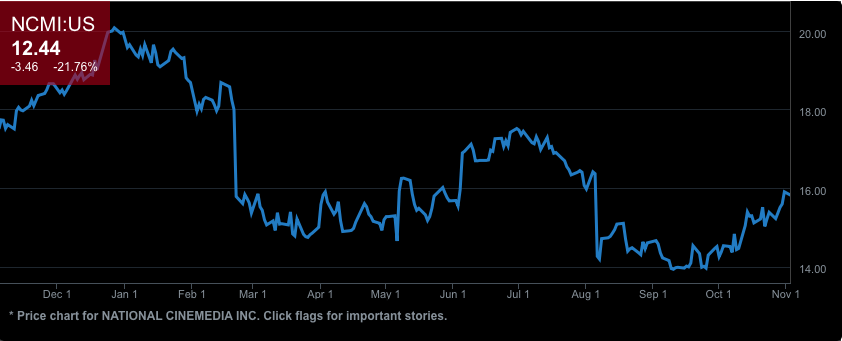

National CineMedia’s bullish forecast for Q4 movie theater ad sales – and vigorous defense of its $375M merger plan with Screenvision — helped its shares regain a little bit of the ground lost today after the Justice Department challenged the deal. The stock is up 4.4% in post-market trading, after falling 21.8% during the day. CEO Kurt Hall says, in an earnings report released late today, that his company’s national ad sales have “made a meaningful recovery” with Q4 sales projected to increase 20% versus the same period last year.

“This turnaround reflects an increased focus by media planners on video platforms and higher-quality event programming that delivers ubiquitous national coverage and enough impressions to positively impact the marketing campaigns,” he says. “While this year’s upfront was a good start, our proposed merger with Screenvision will further enhance our ability to deliver what media planners want to buy.” Hall says that Q4 commitments are up 44% with 13 new clients prepared to spend $58M, plus nine that returned from last year agreeing to up their spending by 14%. What’s more, “the auto category was one of our largest upfront increases. This appears to be a shift in strategy” for the industry.

The announcement did not just send NCM shares tumbling, but Carmike Cinemas was also down 11.26% (as a proxy for Screenvision, where the rest of the shares are held by an un-listed private equity company). Bloomberg notes that NCM shares “fell 21.8 percent, to $12.44, in Nasdaq trading.” They since stabilized and re-gained some ground, but it will be interesting to see whether the market has faith that NCM can counter the DoJ’s move.

The Dog That Didn’t Bark – NATO’s Position

As we have seen, because cinema represents such a small part of overall advertising spend, agencies and brands are unlikely to have a strong opinion one way or the other about NCM and Screenvison merging. Not least because they can always take their ads to television or on-line.

The one voice, however, that has been absent in this discussion is the voice of the exhibtion community, which would be most directly affected by the proposed merger. This is particularly the case for medium size and smaller cinema circuits, which have been the ones that NCM and Screenvision have fought over bitterly in the past.

So why is it that the trade body of the cinema community, the National Association of Theatre Owners (NATO), has been silent in this discussion? The truth is that it is caught in a bind. While it represents the majority of cinema circuits in North America, the four largest members (Regal, AMC, Cinemark and Carmike) have a vested interest in seeing the merger approved.

So while the numerical majority of exhibitors could face worse terms if the proposed merger goes ahead – at least according to the DoJ – the companies that hold the largest sway in NATO would benefit, both directly and indirectly. So NATO sits on the sidelines and exhibitors on both sides appreciate the position the group finds itself in, which in fairness only reflects the larger imbalance or dominance by the major circuits.

What would be interesting, though this is unlikely to occur, is if NATO was asked to testify in the coming case. Then such divided loyalties would be in full view. But the fact that the cinema exhibitors’ trade body has not come out against the deal, is a handicap for the DoJ as it builds a case. It will however be interesting to see who they call to testify.