The European Audiovisual Observatory’s traditional Saturday panel at Cannes’ Marché du Film, held this year on 17 May, returned to a timely and contentious question: what makes a European film successful—and how can we create more success stories?

Moderated by Maja Cappello and Gilles Fontaine of the Observatory, the discussion gathered industry experts to reflect on how success is measured in a fragmented yet interconnected European landscape. The conversation tackled both hard metrics—box office performance, profitability, and festival prestige—and softer values, such as cultural impact and diversity. At its heart, the session examined whether the state-funded European cinema model is still fit for purpose in an era dominated by digital disruption and shifting audience behavior.

“We’re all here because we care about European cinema,” Cappello opened, warmly welcoming a packed morning audience. Quoting Robert De Niro’s speech during the opening of this year’s Cannes Film Festival, she reminded the room that art “looks for truth” and “embraces diversity.” But how can this commitment to cultural pluralism coexist with commercial sustainability? Cappello, the Head of the Observatory’s Department for Legal Information, acknowledged the challenge of reconciling these goals in an industry propped up by public funding and burdened with multiple expectations.

Martin Kanzler, Deputy Head of the Market Information Department at the organization, laid out a pragmatic framework to guide the conversation. “Success,” he said, “means meeting a goal.” From this vantage, a film may succeed financially, in terms of audience reach, or through recognition at festivals. Using data from hundreds of financing plans and film performances, Kanzler broke down each metric with sobering precision.

On financial viability, the findings were blunt. Forty-seven percent of European film budgets are publicly financed, with most funds going to development. Assuming an average fiction feature costs between EUR €1-3 million (spanning small, mid-sized and large markets), “Only 1–5% of European films recoup their production costs through theatrical revenues alone,” Kanzler reported. Even after accounting for pre-sales and subsidies, he estimated that no more than 10% break even, a figure that raises fundamental questions about sustainability. “It’s a fair assumption that the vast majority of European films would not qualify as particularly successful, at least in financial terms.”

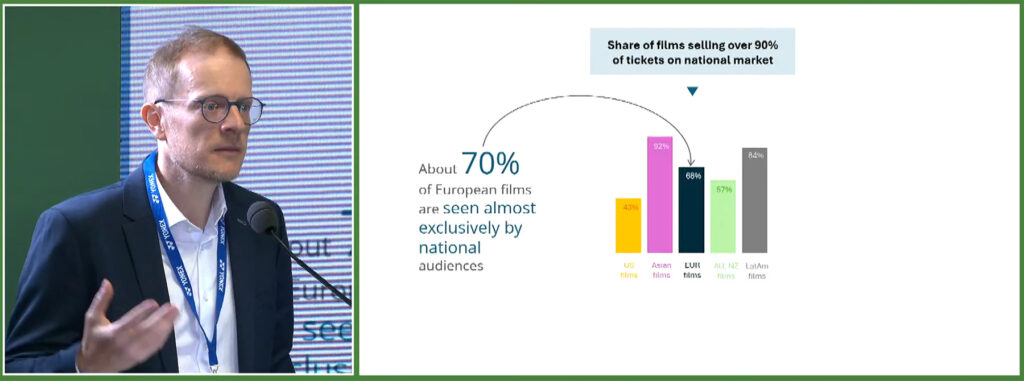

The outlook was slightly brighter when it came to audience reach. Between 2022 and 2024, the average European film drew 210,000 cinema admissions—130,000 nationally and 80,000 outside the country of origin. Kanzler pointed out that while this figure pales in comparison to American or Asian films, it’s still twice that of Australian or Latin American titles. Crucially, most European films are designed for national audiences, with 70% earning over 90% of their admissions in their home markets. “Adjusted for market size,” he noted, “European films actually outperform many others in terms of national reach, but not beyond.”

Festival performance offered the most promising data point. “In terms of festivals, European films are quite successful indeed,” Kanzler reported. From 2018 to 2024, European films represented 55% of all selections at 12 of the 14 FIAPF-accredited festivals—despite accounting for just 31% of global production. “That’s a clear sign of artistic recognition,” Kanzler concluded.

But how do these metrics translate into real-world decisions for those who make, sell, and exhibit films?

Latvian producer Matīss Kaža recounted the arduous journey behind his animated feature “Flow,” which became an unexpected critical darling. Co-produced by Latvia, France, and Belgium, the film’s financing drew on regional funds, tax incentives, and modest minimum guarantees (MGs). “There were a lot of ‘no’s’ along the way,” he admitted, especially from German backers who didn’t believe in a dialogue-free art house animation. “Flow” ultimately premiered in Cannes’ Un Certain Regard—the only animated film in the section—and its international reception was bolstered by a further screening at the Toronto International Film Festival, snowballing from there to eventually earn an Oscar.

“When we were devising the financing plan, box office success wasn’t the goal,” Kaža said. “It was progressive. Trust in the project grew as people saw more of the film.”

Sales agent Valeska Neu of Films Boutique echoed the primacy of theatrical ambition, stating, “When we acquire a film, we need to believe it will do great at the box office.” She said sales agents think simultaneously of distributors and audiences. “Of course, we try to do VOD and TV deals on the sidelines if needed,” she noted.

Neu explained that their business model depends on MGs paid to producers and recouped from distributors. “Our profitability begins when those MGs and marketing costs are recovered. We start with theatrical, but if needed, we’ll look at VOD and TV to make up the rest.”

Still, Neu admits festival launches remain vital. “Cannes is still the peak,” she said. “We need the platform, the press, and the market buzz to get attention. From there, everything follows.”

For Huub Roelvink, founder of Benelux-based Cherry Pickers, theatrical also remains the backbone of the business. “Seventy-seven percent of our revenue comes from cinemas,” he said, adding that MGs can run high in the competitive Benelux market. “We’re probably the riskiest part of the value chain. One flop hurts—but a success like ‘No Other Land’ makes it all worthwhile.”

Swedish exhibitor Peter Fornstam of Svenska Bio emphasized the importance of long-term audience cultivation. “We live by butts in seats,” he said plainly, “but we’re also part of an ecosystem. If only exhibitors make money, that’s no good either.” Fornstam argued that festival wins help, but they don’t guarantee commercial success. “Not every Cannes title draws a crowd,” he said. “Theatrical gives value to a film, but success in the cinema still depends on curation, timing, and luck.”

The conversation then turned to public policy—a complex thicket of national and European directives, quotas, incentives, and funding schemes. Sophie Valais from the Observatory unpacked the Audiovisual Media Services Directive (AVMSD) and its national adaptations. Across the EU, over 47% of film budgets come from public sources, including direct funding and tax incentives. Smaller countries depend even more on these mechanisms, with Latvia, for instance, covering up to 66% of budgets with public support.

In Kaža’s case, Latvian institutional backing helped secure the project’s lead producer status. “It was a sign of trust,” he said. “And it gave confidence to international partners.”

Yet concerns emerged about whether the current funding model favors volume over impact. “We had 2,514 feature films made in Europe last year,” noted Cappello. “Is that too many?” Fornstam argued yes. “Less is more,” he said, applauding the Swedish Film Institute’s plan to back fewer projects with greater resources. Roelvink acknowledged the challenge: “You can’t see everything. There are great films getting lost. But the system still functions—more or less.”

Diversity and accessibility were also recurring themes during the panel. Agnieszka Moody of the British Film Institute spotlighted initiatives like the organization’s “Escapes” program, which offers free screenings in under-served communities. “We’re trying to attract people who normally don’t go to the cinema,” she explained, noting that only 40% of BFI’s funding supports production. The remaining 60% goes to distribution, training, heritage, and audience development.

Finally, the panel acknowledged the elephant in the room: the streaming platforms. While some streamers, like Amazon, now support theatrical releases, others remain ambivalent or even hostile. “The ecosystem only works if we all support each other,” said Neu. Roelvink added, “We need to encourage streamers and broadcasters to license existing cinema films—not just make their own content.”

The panel ultimately demonstrated that striking a more balanced definition of success remains crucial. As the session wrapped, the audience was reminded that European cinema’s success cannot be judged by a single metric. Instead, it lives at the intersection of commerce, culture, and policy. The real challenge lies in creating support mechanisms that are resistant to misuse—something Europe’s funding landscape has not always managed to prevent. At the same time, the limited cross-border circulation of titles speaks volumes. In this context, public support should not reinforce insular storytelling, but rather nurture works that, while rooted in local identities, engage with universal themes and resonate more widely—ideally without falling into predictable, bourgeois tropes.

Luckily enough, festivals continue to serve as essential launchpads, yet the ongoing proliferation of such events risks fragmentation and reduced visibility. In fact, the quality-versus-quantity dilemma can no longer be avoided. If a high-calibre title like “Flow”—rich in artistry and ambition—has lower expectations at the start, what does that mean for less resourced filmmakers? As calls for public backing intensify, the imperative to preserve artistic independence grows stronger. Encouragingly, these debates involving industry stakeholders and policymakers are gaining traction. With thoughtful calibration, they may yet help shape a more resilient and inclusive European film ecosystem.

Ultimately, success in Europe is not just about numbers. It’s about identity, reach, and resilience. And if the story of “Flow” proves anything, it’s that even the unlikeliest project, with enough belief and support, can carry European storytelling far beyond its borders.

J. Sperling Reich contributed reporting to this post.

- Imperfect Is Beautiful: Shekhar Kapur and Tricia Tuttle on AI’s Role in Cinema’s Next Act - December 9, 2025

- Industry Panel at Tallinn Debates the Consequences of Europe’s Shrinking Theatrical Windows - December 2, 2025

- Moviegoers Return But Italian Cinema is Running Out of Stories, Say MIA Panellists - October 22, 2025