By the beginning of September, Cineworld Group’s potential bankruptcy was so widely reported and broadly anticipated that when the company officially filed for Chapter 11 protection on 7 September, most major media outlets buried their coverage in the business section. Few, if any, of the news stories went beyond rehashing the facts laid out in the bankruptcy filing itself. Here, however, we will examine some of the finer points of Cineworld’s bankruptcy in an attempt to provide some analysis for what it all means for the company and the industry-at-large.

The first of this three part series will fill in some of the blanks about the bankruptcy process Cineworld has now embarked on and some of the subtleties that are often glossed over. The second part of the series will lay out the road ahead for Cineworld as it moves through the bankruptcy process. The third part will review the affect Cineworld’s bankruptcy will have on other stakeholders in the market , not to mention what happens to the company’s shareholders.

Just The Facts

First, let’s review and expand on some relevant details in a way that might fill in some minutia. By now, everyone knows Cineworld, the world’s second largest movie theatre operator, with 9,139 screens in 747 sites across 10 countries including the United Kingdom, the United States, Europe and the Middle East, filed for Chapter 11 in U.S. Bankruptcy Court in the Southern District of Texas. The exhibitor made the move in an effort to “implement a de-leveraging transaction” which will reduce its debt and restructure its finances. That debt, as of June of this year, amounts to USD $5.16 billion, or $10.35 billion net debt which includes lease liabilities.

The bankruptcy only covers Cineworld’s holdings in the UK, the US and Jersey and does not affect its operations in Europe. Prior to its filing, Cineworld secured roughly USD $1.94 billion in loans from existing lenders, funding that, according to Cineworld, would be used to maintain ongoing operations at its cinemas, including Regal in the United States, Picturehouse in the United Kingdom and Yes Planet in Israel. The exhibitor “expects to operate its global business and cinemas as usual without interruption.” Its shares, which are down over 86% this year, will continue to trade on the London Stock Exchange as Cineworld restructures. The company plans on emerging from bankruptcy in first quarter of 2023.

The money quote that most publications went with came from Mooky Greidinger, Chief Executive Officer of Cineworld. “The pandemic was an incredibly difficult time for our business, with the enforced closure of cinemas and huge disruption to film schedules that has led us to this point,” he said. “This latest process is part of our ongoing efforts to strengthen our financial position and is in pursuit of a de-leveraging that will create a more resilient capital structure and effective business.”

Greidinger was reiterating what Cineworld has previously stated on 17 August; between pandemic production delays and theatrical titles heading to streaming, the release schedule over the last quarter of 2022 is looking rather slim. What was only being alluded to in his comments was that Cineworld is not the only movie theatre chain that has run upon hard times after the COVID pandemic shuttered cinemas for the better part of a year. Austin, Texas based Alamo Drafthouse and Dallas-based Studio Movie Grill also entered and exited Chapter 11 after the pandemic ground their businesses to a halt. Pacific Theatres and Arclight Cinemas went the Chapter 7 route and liquidated their companies.

Bankruptcy Is A Legal Process

So why didn’t the stream of news stories dive into the nitty gritty details or serve up any analysis on Cineworld’s bankruptcy filing? Well, in part because mainstream media outlets are meant to be objective, but more specifically because Chapter 11 bankruptcy is a complex and at times tedious process with strict rules and regulations. It can be boring and time consuming. Besides, most journalists, including this one, aren’t bankruptcy attorneys. Fewer still want to do the research to understand the road Cineworld is now headed down in order to help translate the filing or provide a cursory examination. Except this one.

Cineworld filed for voluntary Chapter 11 bankruptcy, which means the company went to the court of their own accord to seek protection from creditors. The creditors did not go to the court and force Cineworld into bankruptcy. Once filed, an “automatic stay” stops Cineworld’s creditors from trying to collect amounts owed. All requests for payment, evictions or foreclosures, debt collections, property seizure, bank levies, etc. are all temporarily halted.

Thus, all those landlords looking to kick Cineworld or Regal out of theatre properties for unpaid rent during the pandemic will have to hold off. Equipment manufacturers, concession vendors and service providers will all have to wait to get in touch about their past due bills. That also goes for studios and distributors looking to collect any film rental that might be owed.

After the filing, Cineworld became a “debtor-in-possession” (DIP) meaning they maintain control of the company and run day-to-day business operations while reorganizing. However, from now until when Cineworld exits bankruptcy, the company will not be able to make certain decisions without court approval. Most importantly these include the sale of any assets, starting or terminating rental agreements and signing off on any loans or financing taken on by the company. This came into play on the very first day Cineworld showed up in court.

First Day Fireworks

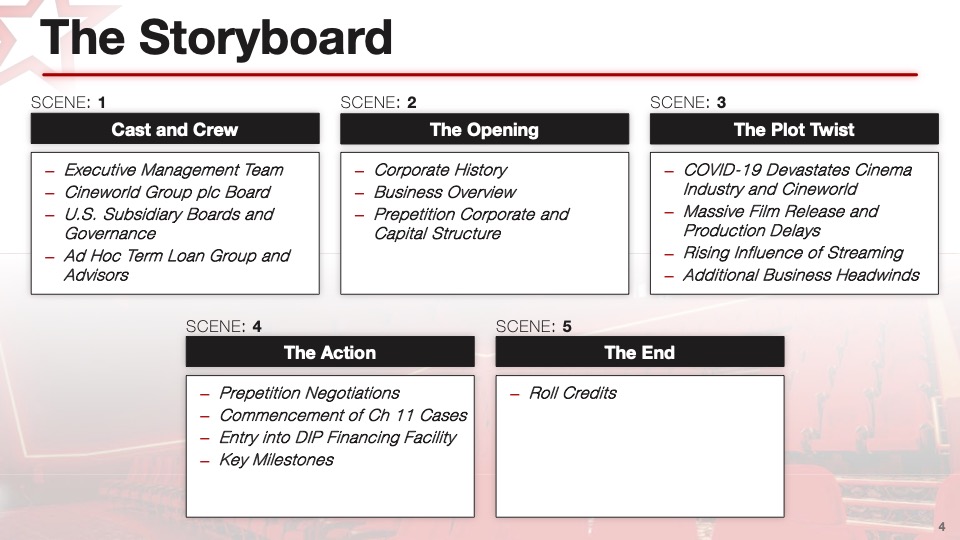

As part of any Chapter 11 filing, a company must immediately appeal to the court in what are known as “first day” motions. This is when a DIP seeks authority from the court to continue ongoing operations with minimal or no disruptions. At this stage, even something as routine as renewing insurance policies or paying employees needs to get approval. That is exactly what Cineworld did on Thursday, 8 September, laying out their path to filing for bankruptcy the way anyone in the movie business might; with a storyboard detailing different scenes, key cast and crew members and even plot twists.

For those well versed in the exhibition business, Cineworld’s backstory is already well known and the recent history of how the pandemic affected the industry need not be rehashed here, though it was likely helpful to US Bankruptcy Judge Marvin Isgur. Like any good movie, the presentation even came with a slide of end credits.

Rather than being amused Judge Isgur immediately prevented Cineworld from gaining access to that previously mentioned USD $1.94 billion loan. That’s because he discovered most of that new loan was going to pay back old debt. During the proceedings the bankruptcy consultancy that the company had hired, AlixPartners, seemed shocked the judge would object to the loan since Cineworld had only USD $4 million in cash which was “not sufficient to run a global operation.”

Rather than be pressured into ruling on a case that had been filed only a day earlier, Judge Isgur said he wanted lenders and Cineworld to come up with a better plan for the funds which reserved USD $1 billion until the company’s immediate cash needs and operating capital was solidified. In that regard the judge was making sure Cineworld has enough money to move forward, not pay for what has already happened. “I am not going to sleep until we get those employees paid tonight,” he said at the time.

By the end of their first day in court, Cineworld and its lenders had restructured their deal so that the repayment of the USD $1 billion in old debt would be delayed until 31 October giving the company a chance to find alternative sources of financing with, perhaps, more favorable terms. That was made slightly more difficult since the judge also insisted that anyone willing to lend Cineworld money would be offered a high guaranteed yield of 20% or higher. On the plus side, if central banks keep raising interest rates to tamp down inflation, that exorbitant level could look like a bargain at some point.

More immediately, Judge Isgur let Cineworld walk out of court with access to three quarters of a billion dollars in operating capital. As the company stated at the time:

As part of these motions, the Court today granted the Group immediate access to up to approximately $785 million of an approximate $1.94 billion debtor-in-possession (“DIP”) financing facility that, together with the Group’s available cash reserves and cash provided by operations, is expected to provide sufficient liquidity for Cineworld to meet its ongoing obligations, including post-petition obligations to vendors and suppliers, as well as employee wages, salaries and benefits programs. The remainder of the DIP facility will become available upon Court approval on a final basis.

Cineworld Press Release

And Then What Happens?

Cineworld continues to operate as normally as possible, paying for rent, goods and services, employees and any amounts owed that are generated during the course of the Chapter 11 process; from 7 September onward. One main difference is that the company will have to seek approval from the bankruptcy court for any activity which doesn’t fall within normal business operations, such as asset sales or post-petition loans.

At the same time the company will be working with its bankruptcy attorneys and consultants to create a plan of reorganization which will propose how Cineworld will pay back their creditors, even if they intend to only pay back a portion of what is owed. The exclusive right for a debtor like Cineworld to submit their reorganization plan usually lasts 120 days, though that time frame can be extended, with court approval, to 18 months.

Simultaneously, any creditor that believes Cineworld owes them money can come forward and file a claim detailing what they are owed. This can include investors, landlords, government bodies, employees, utility companies, vendors, service providers and, yes, motion picture studios.

Keep in mind however, not all claims or creditors are created equal in bankruptcy. Secured creditors, like financial institutions who lent Cineworld money, have a lien against the company meaning they get paid back first and can even force the sale of assets in order to recoup loans in full. They can also collect interest, administrative fees and additional rights during the bankruptcy process. To maintain control and priority during the process, these creditors are usually the first to offer post-petition DIP financing.

After secured lien holders, the administrative expenses are the next creditors to be paid. These are the lawyers and consultants facilitating the bankruptcy for Cineworld. The vendors, landlords, litigation claimants, etc. are all considered unsecured creditors who are between fourth and sixth in line for payment depending on the number of senior creditors ahead of them. The higher up the waterfall of payments a creditor is, the more likely they are to be paid in full. There are ways for vendors to seek critical vendor status and get better recovery terms and major Hollywood studios have already done so.

By the way, shareholders are at the bottom of this waterfall of recovery as the last to be paid, since they are considered owners of the company. The Greidinger family owns 20% of Cineworld’s shares.

When Cineworld petitioned the court for Chapter 11 protection the company submitted a consolidated list of its 30 largest unsecured creditors. The list is filled with names anyone working in the exhibition industry would recognize:

- Christie Digital Systems – $5.8 million – Equipment & Services

- Cinionic – $8.6 million – Equipment & Services

- CJ 4DPlex – $3.4 million – Equipment & Services

- IMAX – $11.3 million – Film Distributor

- Lionsgate Film – $15.1 million – Film Distributor

- Royal Paper Corporation – $3.5 million – Concessions Supplies

- Sony Pictures – $3.3 million – Film Distributor

- Walt Disney Company – $12.1 million – Film Distributor

- Universal Pictures – $20.5 million – Film Distributor

- Warner Bros. – $7.7 million – Film Distributor

- Vistar – $12.2 million – Concessions Supplies

Noticeably absent from this list of creditors is Cineplex Entertainment, the leading Canadian movie theatre chain which Cineworld attempted to acquire in 2019. After Cineworld called off the deal in 2020, Cineplex sued the UK company and a Canadian court awarded the company USD $955 million in damages. Absent a reversal on appeal, that judgement now becomes a claim in Cineworld’s bankruptcy and Cineplex becomes one of their biggest unsecured creditors. This could become a critical factor in Cineworld being able to successfully exit bankruptcy.

The deadline for filing a proof of claim in Cineworld’s bankruptcy is 17 January 2023. As creditors with claims against the company come forward, the court will have the Office of the United States Trustee appoint a committee of major unsecured creditors to represent and negotiate with Cineworld on behalf of all unsecured creditors; the Official Committee of Unsecured Creditors (UCC). The trustee requests a willingness to participate in the committee from the top 20 unsecured creditors. It can be a bureaucratic and time consuming process in which those willing to participate the trustee will select representatives from creditors owed the largest amount.

Cineworld’s bankruptcy case is moving so swiftly that the Trustee assigned members of its UCC before the writing of this piece could be complete. They are as follows:

- Cineplex Inc. – representing litigant plaintiffs with claims

- The Bank of New York Mellon – representing landlords

- Paramount Pictures – representing studios

- Simon Property Group, Inc. – representing landlords

- PepsiCo Sales, Inc. – representing concession vendors

- CJ 4Dplex Americas, LLC – representing equipment manufacturers

- Land Securities Properties Limited – representing landlords

- EPR Properties – representing landlords

- Realty Income Corporation – representing landlords

- Intertrust Technologies Corporation – representing litigation plaintiffs with claims

The reason to establish the UCC is because all unsecured creditors, also known as a class of creditors, will recover their claim at the same rate. Meaning, if Vistar collects 10% of what it is owed as an unsecured creditor, so will all the other unsecured creditors. Therefore, they have to reach an agreement with the debtor that a majority, if not all, of the entire class of unsecured creditors is willing to accept. These discussions commence within 60 days of a bankruptcy filing at a meeting of creditors known as a Section 341 meeting.

Part 2 of the series lays out the road ahead for Cineworld as the company moves through the bankruptcy process. In Part 3, we will look at what bankruptcy means for Cineworld shareholders, as well as a few potential outcomes for the company as they move through bankruptcy.

- A Quiet Player Makes a Big Move: Qube Cinema Acquires Arts Alliance Media - February 23, 2026

- As Sundance Says Goodbye to Park City, Its Films Look Forward - January 21, 2026

- Opening Night at the 2025 Red Sea Film Festival Showcases Saudi Arabia’s Growing Cinematic Ambition - December 5, 2025