On 7th July, cinema advertising company Digital Cinema Media (DCM) hosted their UpFronts Showcase at the Odeon Luxe in London’s Leicester Square. The morning’s presentations focused around a theme of “cinema as attention leader” (not the official title) and a data presentation was given to support this concept by Lumen Research. A further deep dive into why this is the case then came from UCL (University College London) cognitive neuroscientist, Professor Joe Devlin, who presented his team’s research into “Why Cinema is Designed to Make a Lasting Impact” (actual title).

There followed a short, succinct presentation from Devlin into a breakdown of the five elements involved in cinema-going that result in said impact being made:

1 – A Unique Location

Leaving the house to visit the cinema primes the brain’s hippocampus into laying down new memories (one of the hippocampus’ core functions). Attending a cinema venue stimulates the hippocampus in this way – by being somewhere new and out of the house – but also builds anticipation for the film you’re about to see, so your brain is expecting something different and interesting to happen, resulting in memories being made that will stick and last.

Thinking back to the pandemic lockdowns, many of us suffered (and perhaps still do) from “brain fog” and a sense of groundhog day. Professor Devlin explained that this feeling was a – not uncommon – experience brought about by the lack of day-to-day stimulation. The only physical movement many of us saw all day was between the different rooms of the house, which provided no stimuli to create new memories.

2 – No Distractions

Multitasking at home has become a way of life for many of us as we juggle navigating our way between social media, choosing which content to watch on a thousand different platforms, conversing with friends and family, and, of course, our work. This means the central executive of the brain is constantly switching between tasks. Professor Devlin explained that the brain can lose up to 40% (!) of cognitive capability when we’re in this mode of switching between things, making it far harder to do a good job on any one of them.

But in the cinema the environment, and the intention of being there in the first place, creates a very different dynamic. Phones are put away (or should be!), and 100% attention is given to the screen, with this being exactly why cinemas have been termed “digital refuges”.

3 – Sharing the Experience

However much of an introvert or an extrovert you are, the human condition is a social one and the act of watching a film at the movies with a live audience is considerably different to watching one alone at home.

The autonomic nervous system, which is responsible for the fight or flight response, increases around other people so the brain is being essentially primed to produce stronger reactions to whatever you’re experiencing when you’re with a large, live audience vs watching alone or with a smaller group.

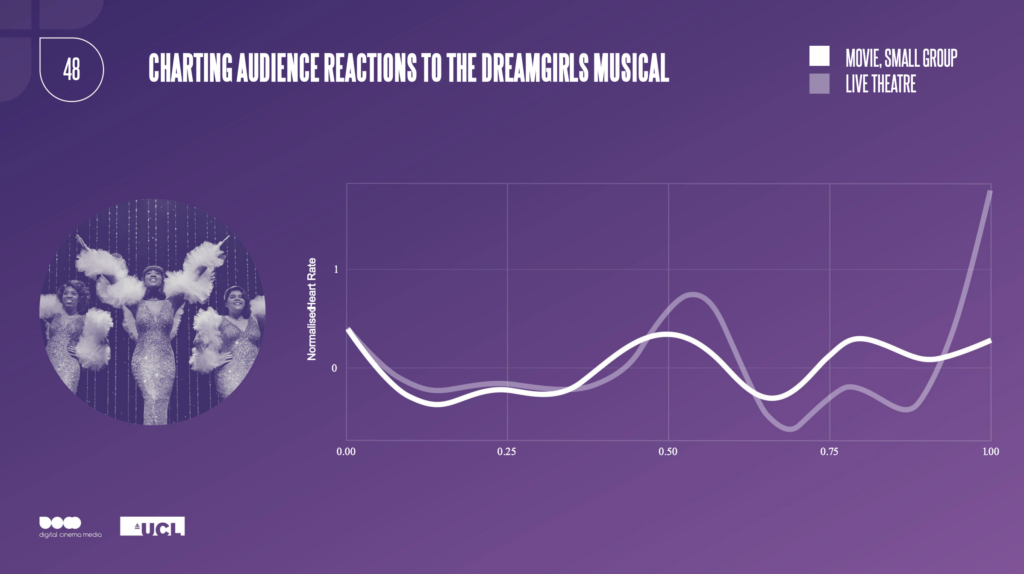

To illustrate exactly this, an experiment was conducted at a live performance of “Dreamgirls” in London’s West End. Audience members were given a heart rate monitoring device (think FitBit or Apple Watch) to wear while they watched the show, with the expectation being that, while sitting and at rest, the heart rate would (or “should”) be a flat line.

Not so. The results showed peaks and troughs mirroring the narrative of the show. By the end of the two-and-a-half-hour performance the recorded heart rates were in the range of the British Heart Foundation’s “light cardio activity” category, due to the emotional connection formed with what was happening on stage.

To further demonstrate this, Professor Devlin carried out a smaller test with a group of six people in his lab watching “Dreamgirls”, but this time on film. Again, all wore heart rate devices and again, their heart rates similarly mirrored the peaks and troughs of those who watched the live show – but the reactions weren’t as strong when compared to the much larger Savoy Theatre audience.

4 – Tell Me a Story

An obvious statement this may be but cinema is the home of storytelling. And studies have shown that, when recounting information whether anecdotal, educational or other, stories are a far more powerful way of communicating. In fact, they’re 50% more effective than simply listing facts.

Devlin shared an example of this whereby a cohort of ER (Emergency Room) doctors attending a medical conference were studied, focusing on the prescription of opioid pain medication. The US FDA (Food and Drug Administration) created six new guidelines necessary for these prescriptions that they wanted the doctors to memorise and implement. The cohort was split into two groups, one of whom was given a list of straightforward facts about the drugs and the other was given a one-page sheet detailing a narrative in story format on the same topic.

At the end of the conference the doctors were quizzed and the results showed the narrative story group retained 50% more information than the other group.

5 – A Big Ol’ Screen

Perhaps the most obvious element to cinema-going that provides the “wow” factor and creates a lasting impression is the size of the screen (and accompanying audio / visual technology).

Professor Devlin explained that the larger the picture is, the larger the part of your brain that engages, creating more brain activity and, you guessed it, lasting impact. Compared to watching a film on your phone screen, research has shown that cinema audiences have a greater external focus of 33% and pay more attention to a larger screen than a small one.

An Attention Commander

A final relevant experiment to mention here is Professor Devlin’s work carried out with Vue International. Audiences who came to see the live action film “Aladdin” were monitored with “wear and forget” technology (similar to the kit previously mentioned) for a set of physical reactions (body temperature, electrodermal activity and heart rate) to different parts of the story. One notable response was when Jasmine and Aladdin share a kiss at the end of the film, with audience electrodermal activity (the property of the human body that causes continuous variation in the electrical characteristics of the skin) rising to its highest point. Not a surprising ending – I think we’re all familiar with the Disney formula by now – but still one that elicited such a response, en masse.

As Professor Devlin said, and has explored through his studies, the cinema environment really is a special one for cultivating emotional responses. Given our focus here at CJ, we can’t help but agree.

- A 10th Anniversary, Theatrical Smash Hits, and a K-Pop Takeover - February 10, 2023

- CJ Interviews: Really Local Group - November 30, 2022

- The Science Behind the Impact of Cinema - August 4, 2022