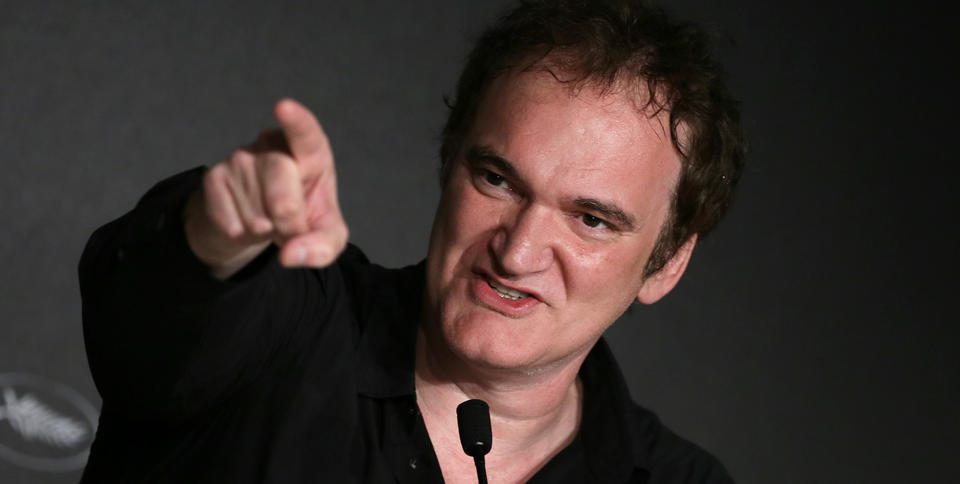

As the 67th annual Cannes Film Festival came to a close last week, artistic director Thierry Fremaux scheduled a last minute press conference so that journalists from around the world could speak with filmmaker Quentin Tarantino. The director was visiting the festival for a 20th anniversary screening of his second feature, “Pulp Fiction”, which premiered at Cannes in 1994 and won its top prize, the Palm d’Or. It’s a safe bet nobody predicted the lead story coming out of Tarantino’s 48 minutes with journalists would be about digital cinema and serve to underscore the learning curve film festivals are grappling with when it comes to the new technology.

Yet, every year in Cannes there is at least one press conference where a filmmaker or actor says something that gets tossed into the media echo chamber and published around the globe en masse. Director Lars von Trier’s comments about Nazis a few years back are a perfect case in point. In 2014, the honor went to Tarantino, whose animated, hyperactive Cannes press conferences are the stuff of legend. This year he managed to bolster his Cannes cred after negative comments he made about digital cinema were turned into headlines by every major media outlet in all languages.

As Fremaux pointed out while introducing Tarantino, the filmmaker’s name is closely tied to Cannes and the year “Pulp Fiction” won the Palm d’Or is an important milestone in the festival’s history. That is why Tarantino was asked to participate in a press conference, an activity usually reserved for filmmakers with movies premiering in Cannes. Fremaux also noted that “Pulp Fiction” was the only title in the festival to be projected using 35mm film. “Everything else is DCP, digital,” Fremaux reported. “But obviously we wanted this film to be shown in 35mm.”

With that said, it didn’t take long for Tarantino to turn his attention, not to mention his ire, toward digital cinema. “As far as I’m concerned digital projection and DCPs is the death of cinema as I know it,” Tarantino proclaimed. “The fact that most films now are not presented in 35mm means that the war is lost. Digital projection, that’s just television in public. Apparently the whole world is okay with television in public, but what I knew as cinema is dead.”

After comments such as that, you can only imagine how many headlines screamed “Tarantino Declares Cinema Is Dead”. More than likely you’ve already seen a few of the thousands of stories in which the filmmaker’s comments on the subject are extensively quoted.

“I’m hopeful that we’re going through a woozy romantic period with the ease of digital and I’m hoping while this generation is completely hopeless that the next generation will demand the real thing,” he continued. “I’m very hopeful that future generations are much smarter than this generation and realize what they’ve lost.”

Well, sadly Mr. Tarantino, we advise that you not hold your breath for such a moment to arrive. It is one thing for vinyl record albums to make a comeback among audiophiles who race out to purchase turntables to play them. It is an entirely different scenario for commercial entities such as movie theatres to re-adopt technology to work with a historic distribution method. Sure, specific venues here and there will still have a 35mm projector to screen mostly archival prints; think museums, film schools and specialty art houses. But it took 15 years for a multi-billion dollar industry to make the conversion to digital cinema and a film based infrastructure is simply no longer in place to produce, process and distribute films in 35mm.

At the very least, replacement parts for analog cinema equipment will become difficult to obtain. So will skilled projectionists trained to use 35mm equipment.

A digital future was never more evident than at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, where at times the need to screen DCPs using the latest, greatest digital cinema technology managed to cause a few hiccups. On the very first evening of the festival, in the midst of the press screening for Abderrahmane Sissako’s competition film “Timbuktu”, the image being projected onto the giant 15 meter (50 foot) screen posterized and bitmapped, obscuring the exquisite cinematography. The problem lasted for about 20 seconds before a faint grid patter briefly appeared and the image completely froze before it returned to normal. It took another 30 seconds for subtitles to start showing up on screen again. The issue lasted roughly a minute, though came during a crucial moment in the film’s storyline.

Trying to speak with the projection team responsible for the official Cannes screenings was difficult since they are naturally very busy during the festival. The one projectionist I managed to get hold of informed me errors such as the one that occurred during the screening of “Timbuktu” usually had something to do with the mastering of a DCP rather than an equipment failure. Christie Digital, Dolby and Doremi were all official technical partners of the festival and their representatives were on site at all times to assist with any issues that arose with competition screenings.

It was neither mastering nor equipment problems that caused subtitle issues during of “The Homesman”, A western directed by award winning actor Tommy Lee Jones. As the film began the timing of the French subtitles was off causing them to overlap and thus be unreadable. Though it might at first seem that subtitles rendered by CineCanvas might be the culprit, given how quickly the glitch was rectified (two minutes) it is more likely that the timed text file accompanying the DCP was inaccurate.

Unfortunately such speed bumps weren’t always solved so quickly, as was the case when two-thirds of the way through a showing of “Life Itself” the audio system blurted out a loud pop before the screen went green and ultimately dark. To everyone’s surprise, there was nobody in the projection booth at the Salle Buñuel where the documentary on the life of film critic Roger Ebert was being screened in the Cannes Classics section of the festival. Thankfully Chaz Ebert, Ebert’s widow and CEO of The Ebert Companies, was present in the audience. She accompanied director Steve James (“Hoop Dreams”) to the front of the theatre for an impromptu question and answer session which lasted for the 30 minutes it took to resume the screening.

And while these occurrences might make it look as if digital cinema is causing more problems than it’s solving, keep in mind that in the more than 15 years I’ve been attending the festival I have witnessed my fair share of projection issues with 35mm. For instance, at the 2006 festival the press screening of Alejandro González Iñárritu’s “Babel” was briefly interrupted when an improperly labeled reel was projected out of sequence, repeating earlier portions of the film. Of course, there were always broken sprocket holes causing jittery registration or prints without French or English subtitles burned in. These are troubles that projectionists historically ran into during the days of 35mm, no matter the venue or festival. Cannes however was usually quite expeditious in fixing the cause of any problem and over the years has built a reputation for pristine screenings.

In other words, the projection snafus with digital are no greater in number than what occurred with 35mm. It’s just that they are different in nature and when they occur are far more abrupt. Unlike 35mm which can keep running an out of focus or misaligned image, there is no grey area with digital equipment; it either works or it doesn’t. As noted, the Cannes Film Festival is probably in one of the best positions to overcome any digital hurdles. As the largest event of its kind in the world they staff some of the most adept projectionists in France (if not Europe) and have tons of assistance from industry leading digital cinema firms. Not every film festival has such luxuries, yet they are all facing the same issues and learning curves.

At the very least digital projection probably alleviates some of the logistical headaches Cannes previously contended with. For example, moving content around has likely been made much easier since they no longer have to worry about lugging heavy 35mm film reels between venues. Even Tarantino acknowledged some of the benefits digital has to offer.

“The good side of digital is the fact that a young filmmaker can actually now just buy a cell phone and if they have the tenacity to come up with an interesting story and get some interesting actors, or not, and put something together, they can actually make a movie and that film can go on the film festival circuit and they can be legit, they can be real,” said Tarantino. “Back in my day you at least needed 16mm to do something like that which was a Mt. Everest most of us couldn’t climb. That’s me talking out of the other side of my mouth saying the good part about it all, especially for younger filmmakers. Now, why an established filmmaker would shoot on digital I have no f***ing idea. I don’t get it at all.”

- Edinburgh Filmhouse Secures 25-Year Lease, Announces New Patrons - July 11, 2024

- Mixed Results for Global Box Office During First Half of 2024 - July 10, 2024

- George Rouman, Cinema Operator and Industry Champion, Dies at 51 - June 13, 2024