As we begin the new year, I strongly believe we are entering a period of great danger and even greater uncertainty. Events are unfolding within and without the movie industry that are extremely threatening to our studio.

This is how Jeffrey Katzenberg began his now infamous 1991 memo which criticized the Walt Disney Studios, of which he was then chairman, and the overall state of the film business at the time. It’s hard to believe those words were written more than 20-years ago since they are so easily applicable to the current motion picture business.

Katzenberg penned his prophetic memo in 1990 during a rainy Christmas vacation in Hawaii. The end-of-year holidays are often a time of increased introspection on a multitude of subjects that range from personal to professional, from political to religious. A few consecutive days with a couple of extra unoccupied hours and and we all turn into armchair Nietsches. Like Katzenberg, I also came to a bit of a realization during our recent holiday season about the industry we all passionately toil away in.

Actually, if recent introspective pieces by Nick Dager at Digital Cinema Report and Luke Edwards at Pocket Lint are any indication, I’m not the only one who spent the holidays ruminating about the present and future of our business. These constructive assessments present qualitative research to diagnose the recent downturn in moviegoing attendance, attributing the cause to a number of factors, including the emergence of subscription streaming media services. To these treatises I would like to add some academic theorems that can be useful in helping us determine where theatrical exhibition falls on the curve of a typical market’s lifecycle as well as models that are useful in forecasting future market conditions.

Collecting Anecdotal Evidence

Because the mathematics and theories underlying diffusion theory can be dry and didactic, translating them to existing or real-world markets can at times seem confusing. Thus, I will attempt an explanation through an anecdote which initially coaxed my mind down the path of such market musings in the first place.

During the holiday break I witnessed innovation diffusion theory in action through the promulgation and/or unfamiliarity of over-the-top streaming services such as Netflix among extended family members and acquaintances. By applying simplified diffusion theories to this qualitative research I was able to discern the current market complexities and the far-reaching consequences motion picture exhibitors and distributors will undoubtedly face due to growing consumer adoption of online video streaming services.

I spent New Years week in Sun Valley, Idaho, known for some of North America’s best skiing and as the final resting place of Ernest Hemingway. I was with nine members of my extended family (i.e. in-laws) ranging in age from nine to 67. Days were filled with plenty of ski lessons, gondola rides and leisurely lunches. At night, everyone would be back at the comfortable house we had rented for dinner and nightly activities. That usually meant reading magazines, bedtime stories, books, responding to email, trolling Facebook and, after the first night, watching the gorgeous 60 inch LCD television.

Upon arriving, the in-laws informed me that the television in the living room didn’t work. Being the “techie” in the family I was assigned to “fix it”, which didn’t take long. I quickly deciphered which of the two available remotes turned on the power to the TV and which controlled volume, channel selection, the cable box, etc. Within a minute I had the TV tuned perfectly to whatever Sunday football game was on and chose to take the backhanded complement of “finally making myself useful” as well earned in-law adoration.

Noticing the televisions was one of those Samsung Smart TV’s I attempted to connect to my Amazon Prime account. When I was unsuccessful one of the in-laws in her mid-forties suggested I try connecting to her Netflix account. No dice. That’s when it dawned on me the TV might not be connected to the Internet, which I confirmed by poking around at the connections in the back. I found a spare ethernet cable running from the cable box to the router and ran it from the router to the back of the TV instead. Not only did the wi-fi still work, but the TV was now successfully connected to the Internet making it possible to log into my in-law’s Netflix account.

What transpired when everyone wound up in front of the television that first evening is a near-perfect example of diffusion theory, in this case used to define the adoption of over-the-top technology:

- 46-year-old mother – the only subscriber to Netflix was surprised to learn she could terminate her DVD subscription and still get Netflix streaming. This mother of a 5-year-old boy immediately logged in to her account on an iPhone and did just that.

- 49-year-old father – a senior manager at a Fortune 100 company was unaware his family subscribed to Netflix and that his 5-year-old son had his own viewing que. A frequent traveler, he asked how much the subscription cost and was surprised to learn he could watch Netflix on the iPad he always has within arms reach. When streaming video from Netflix hit the screen for the first time his exact words were, “Why would anyone ever go to a movie theatre again?”

- 5-year-old boy – familiar with his mother’s Netflix subscription he began shouting out random titles in hopes everyone would want to watch “Power Rangers”.

- 47-year-old mother – a medical doctor, Ivy League alum and mother of two daughters under the age of 10 asked if Netflix had “Dr. Who”, and if so, whether she could watch it on her iPad while we were watching something else in the living room.

- 8 and 9-year old sisters – since their parents aren’t subscribers they were unfamiliar with Netflix. They were amazed to see all their favorite movies were available. They never requested to watch anything specific because they were too busy making their aunt scroll through the endless list of titles.

- 67-year-old grandfather – a former lawyer and successful businessman who is a voracious reader of the Wall Street Journal, New Yorker and The Economist, asked how much it cost to watch each title. He was surprised to hear everything was all included in the USD $10 monthly subscription. Proceeded to watch every episode of “Marco Polo”, learning first-hand about “binge viewing”, and vowed to subscribe to Netflix as soon as he returned home.

- 67-year-old grandmother – explained she used to subscribe to Netflix, but canceled after realizing she kept the same DVDs for months at a time. She was also unaware Netflix offered a subscription for just the streaming service.

Applying Diffusion Categories

Though far from being an exhaustive scientific survey, this small market sample managed to contain most of the adopter categories; innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, laggards, leapfroggers. These are the key adopters as defined by Everett Rogers who originated the diffusion of innovations theory in 1962.

In a little under ten minutes the group went through an accelerated diffusion process that demonstrated stages of the technology adoption lifecycle.

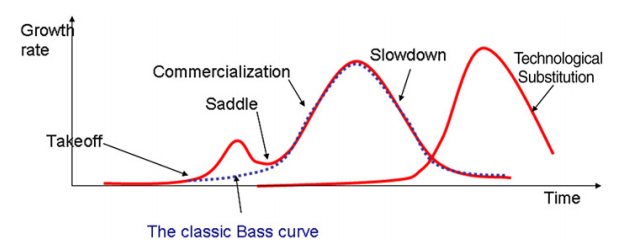

Let’s get geeky for a moment. Traditional diffusion models revolve around work published in 1969 by Frank Bass. The Bass Model provides a differential equation to detail how durable goods get adopted by consumers; new products are introduced to a market (m) and then adopted by influencers due to external influences (p) like advertising or word-of-mouth (q), in turn convincing imitators to purchase the product. One issue with the Bass model is that it assumes an interconnected and consistent social network.

Over time however diffusion innovation models have had to adapt and become more complex, as described in a 2010 academic paper by Renana Peres, Eitan Muller and Vijay Mahajan titled “Innovation diffusion and new product growth models: A critical review and research directions”:

The proliferation of newly introduced information, entertainment, and communication products and services and the development of market trends such as globalization and increased competition have resulted in diffusion processes that go beyond the classical scenario of a single market monopoly of durable goods in a homogenous, fully connected social system.

These more complicated models show a “saddled” adoption curve for new technology innovations rather than the commonly referenced linear curve. In these models the early market is made up of between 10-20% of a products ultimate adopters. In our example the 46-year-old mother and 67-year-old grandmother would be the innovators and early adopters. Despite not having made an actual purchasing decision, the 5-year-old boy could also be considered an early adopter through his accepted use of Netflix.

After initial adoption takes place, there is often a decrease in uptake of the product or innovation before the mainstream market adopts it. Hence the saddle-like dip. This too is shown in our example by the 46-year-old mother and 67-year-old grandmother who had respectively downgraded and canceled their subscription to Netflix.

The struggle for most new technology is bridging the gap (or saddle) between early adopters and the early majority in an effort to reach a mainstream market. Technologist Geoffrey A. Moore has famously dubbed this feat “crossing the chasm”. Early majority adopters make up 34% of the market for most new products. These consumers adopt a technology after innovators and early adopters they know personally have successfully used it.

Every other person in our tiny survey could be considered an early majority adopter since they had just witnessed early adopters benefit from use of an innovation. This would only be true however if they actually adopted the new technology through purchase or use. It would seem the 47-year-old mother will begin using the service. So will the 67-year-old grandfather, who still uses a Blackberry and historically would have been identified as a laggard.

The 49-year-old father is an early adopter by default, though only economically. He has yet to actually adopt the technology by using it, though will probably become a late majority adopter when his wife finally follows through on canceling their cable subscription. The 8 and 9-year-old sisters must rely on their parents to subscribe to Netflix before they can adopt it. If this does not happen they might be able to adopt the technology socially though not financially. As such they will be forced into the late majority or laggard category of adopters and may even completely leapfrog Netflix altogether if a better service comes along in the meantime.

Over-The-Top Jumps Across The Chasm

From our imperfect study we can establish that over-the-top subscription services in the midst of this saddle. This is also evidenced by recent stagnant subscriber growth reported by Netflix. According to diffusion theory, the only way for such services to bridge the saddle is to displace existing technology, innovations, products or platforms.

Netflix and Amazon have been trying to do just that by wooing premium television subscribers with award winning original programming like “House of Cards” and “Transparent”. Netflix may also be attempting to disrupt movie theatres as implied by their plans to produce and distribute a sequel to “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” day-and-date with a theatrical release.

To be sure, Netflix and similar services have had no problem at penetrating the market through the social influence required for successful innovation diffusion. Their original programming is commanding a lot of media attention, awards accolades and has become a part of the cultural dialogue among high-minded techies.

When progressive filmmakers such as David Fincher create content for you, it sends a social signal about how “hip” or “exciting” this new distribution platform is. When that programming goes on to receive rave reviews from leading media outlets and win top industry awards, it makes the early majority aware of just how successful and important over-the-top offerings are becoming. When veteran filmmakers not known for embracing technology or innovation show up to develop content for the platform, there is no mistaking the chasm has been crossed. That was the case this past week, when Woody Allen made front page news by announcing he would produce and direct a television series for Amazon. This is a filmmaker that has yet to adopt stereo audio for his movies, now he’s leapfrogging directly into streaming media.

Yet over-the-top services still suffer a huge obstacle created by what are referred to as network and technological externalities. This was very apparent in our impromptu survey in that roughly 30% of those present knew how to access Netflix streaming service and only one person (myself) knew how to connect the Internet to the television to begin with. That five adults out of six could not figure out how to make the TV work, let alone connect an ethernet cable to it, speaks volumes as to the market’s understanding of the tools needed to adopt the technology.

What All This Means For The Future of Cinemagoing

The external forces that make adoption difficult today are usually overcome to make it easier tomorrow. The necessary comprehension of the technology and resources enabling over-the-top content consumption will eventually not be an issue.

Any equipment that comes within ten feet of a television is a connected-device these days that can, with a modicum of effort, stream Netflix, Amazon, Vudu, etc. to what is increasingly a larger than 60-inch HD television set that presents a beautiful picture. Soon enough, the 67-year-old grandfather in our scenario won’t have to seek assistance to connect a Roku, Apple TV, Chromecast or X-Box to his television in order to watch streaming video because every set will be a Smart TV that can connect to the Internet directly. Other than remembering one’s wi-fi password, technological obstacles be damned.

As reported by Digital TV Research last September, the number of TV sets connected to the Internet will reach 965 million globally by 2020, up from 339 million at the end of 2014. If that holds true, 30% of every television in the world will be connected to the Internet. With such figures and timelines it becomes easier to forecast the disruption this will cause to existing content distribution models.

Television will be the first to get disenfranchised. Just as television hindered the growth of radio listenership and cable providers upended broadcast television networks by fracturing viewership, over-the-top services like Netflix will displace certain aspects of cable. We are slowly begin to see this with the unbundling of certain networks from premium and basic cable packages. This says nothing of how the adoption of streaming media technology has affected the mindset of audiences who don’t care (or even know) precisely when a show airs and expect to receive every episode at the same time.

Lastly, and the primary reason my mind wandered down this path in the first place, the theatrical movie business will ultimately feel the sting of streaming media subscription services. The outcome might not be as drastic as the impact on television, however the long-term effects have the potential to cause a behavioral shift away from regular attending movies in the cinema. Need I remind you of the comment made by our 49-year-old-father?

Moviegoing won’t die off completely. After all, there were theatres in ancient Greece. But it is likely to be altered in ways both known and unclear. In North America we’ve started to see the effect of this as exhibitors try to lure us away from our couches and Netflix subscriptions with plush reclining seats, luxury auditoriums and in-theatre dining. The expansion of IMAX and premium large format screens is another byproduct.

Another reason cinemagoing won’t completely end, simply change, has to do with a point Alejandro Ramirez Magaña, the CEO of Cinépolis, made at ShowEast in 2007. In receiving that year’s International Achievement Award in Exhibition, Ramirez gave an upbeat speech in which he lauded the cinema going experience and disagreed that movie theatres would soon disappear. “As long as people need to go on dates, there will be a need for movie theatres to exist,” he told the audience.

I’d agree with that sentiment, but also add a reminder that those who date eventually grow older, find partners and/or marry, have children and don’t go out on as many dates. Provided the population doesn’t drastically decrease this may not be an issue since there will always be another generation of young couples entering the dating scene.

But the death of cinema and movie theatres has long been predicted by countless doomsayers and yet never come to pass. Which brings us right back to how Katzenberg’s memo can be so prescient two decades after being written. Maybe the more things change, the more they stay the same. Of course, anyone who ever worked at Tower Records may disagree.

- A Quiet Player Makes a Big Move: Qube Cinema Acquires Arts Alliance Media - February 23, 2026

- As Sundance Says Goodbye to Park City, Its Films Look Forward - January 21, 2026

- Opening Night at the 2025 Red Sea Film Festival Showcases Saudi Arabia’s Growing Cinematic Ambition - December 5, 2025